You need to understand a legacy codebase before implementing a feature. Authentication flow, database schema, API patterns — you ask Claude to investigate. By the time you understand enough to act, your context is half full of code snippets you’ll never reference again.

Or you’re mid-implementation and realize you need to check how another part of the system handles a similar case. Stop? Lose your thread. Continue? Risk making bad assumptions.

Investigation fills your working context with stuff you don’t need afterward. Sub-agents keep it separate.

The Context Bloat Problem

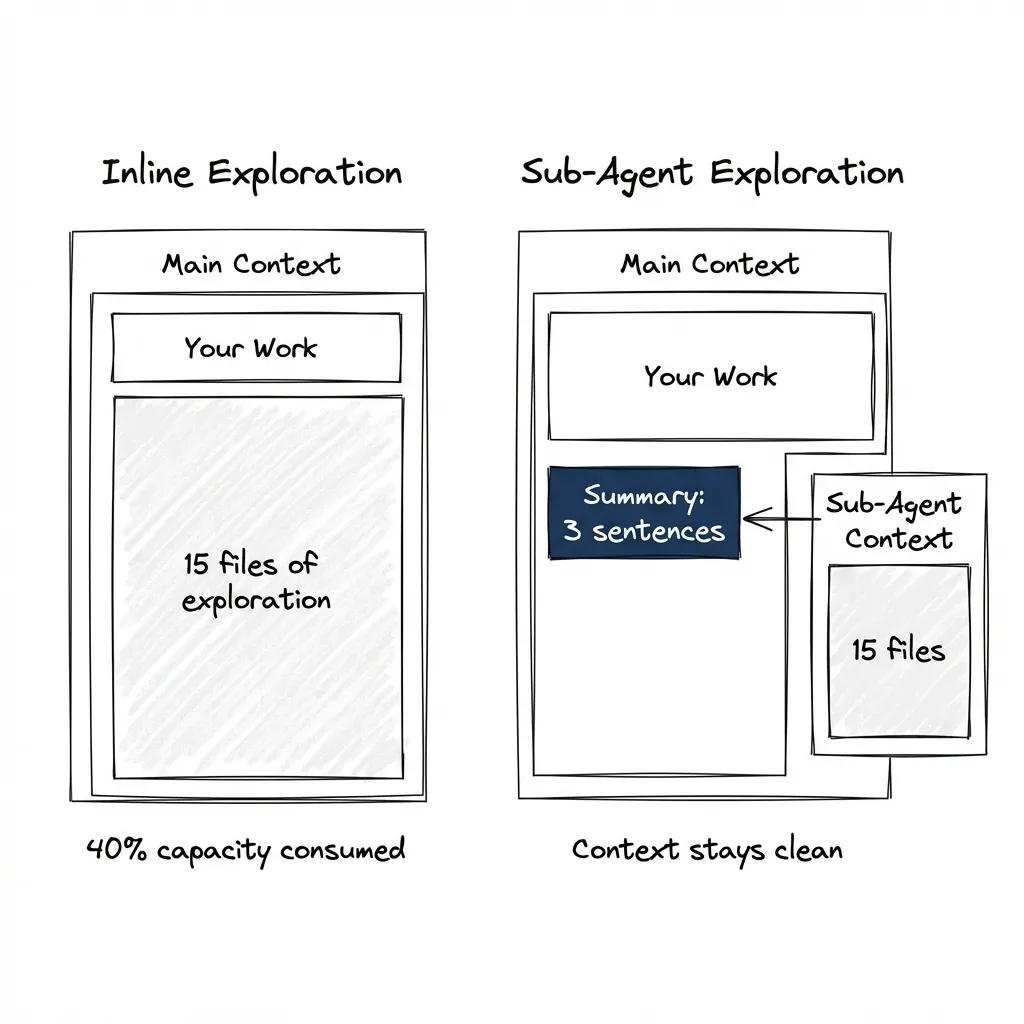

Exploration means reading many files, comparing patterns, building a mental model. The useful output is conclusions — three sentences about how auth works. The intermediate work is large — 15 files of code, dependency chains, config files.

When you explore inline, all that intermediate work fills your main context. By the time you’re ready to implement, you’re already at 40% capacity. The model performs measurably worse near context limits. (I demonstrated this hacking a 43k-star tool — fill context with legitimate-looking content and the model becomes more suggestible.)

Sub-Agents as Function Calls

Think of sub-agents as function calls for reasoning. Send inputs, receive outputs, don’t carry intermediate state.

The pattern:

Main agent: "I need to implement auth middleware."

Instead of exploring inline (fills context with 15 files):

Task(

subagent_type="Explore",

prompt="Find how authentication is implemented. Return: patterns, key files, gotchas.",

description="Explore auth implementation"

)

Explore agent reads files in its own context.

Main agent receives: "Auth uses JWT with refresh tokens.

Key files: auth/middleware.ts, auth/tokens.ts.

Gotcha: token rotation happens client-side."What comes back: summary, not transcript. Conclusions, not journey. Your main context stays clean.

Claude Code has built-in subagents:

- Explore: Fast, read-only. Uses the Haiku model. Optimized for codebase search.

- Plan: Gathers context during plan mode before presenting a plan.

- general-purpose: Full tool access for complex multi-step operations.

When to Fork vs Stay Inline

Fork to a sub-agent when:

- Investigation will read many files you won’t need afterward

- Task is self-contained with clear inputs and outputs

- You need parallel exploration of different areas

- Fresh perspective benefits the task (code review, QC validation)

Stay inline when:

- You’ll need the details for immediate follow-up

- Task is tightly coupled to current work

- Simple lookup — one or two files, quick answer

- Overhead of context transfer exceeds benefit

Rule of thumb: if you’d say “give me a summary when you’re done,” that’s a sub-agent task.

Specialized Agents

Sub-agents with domain-specific instructions baked into their system prompt.

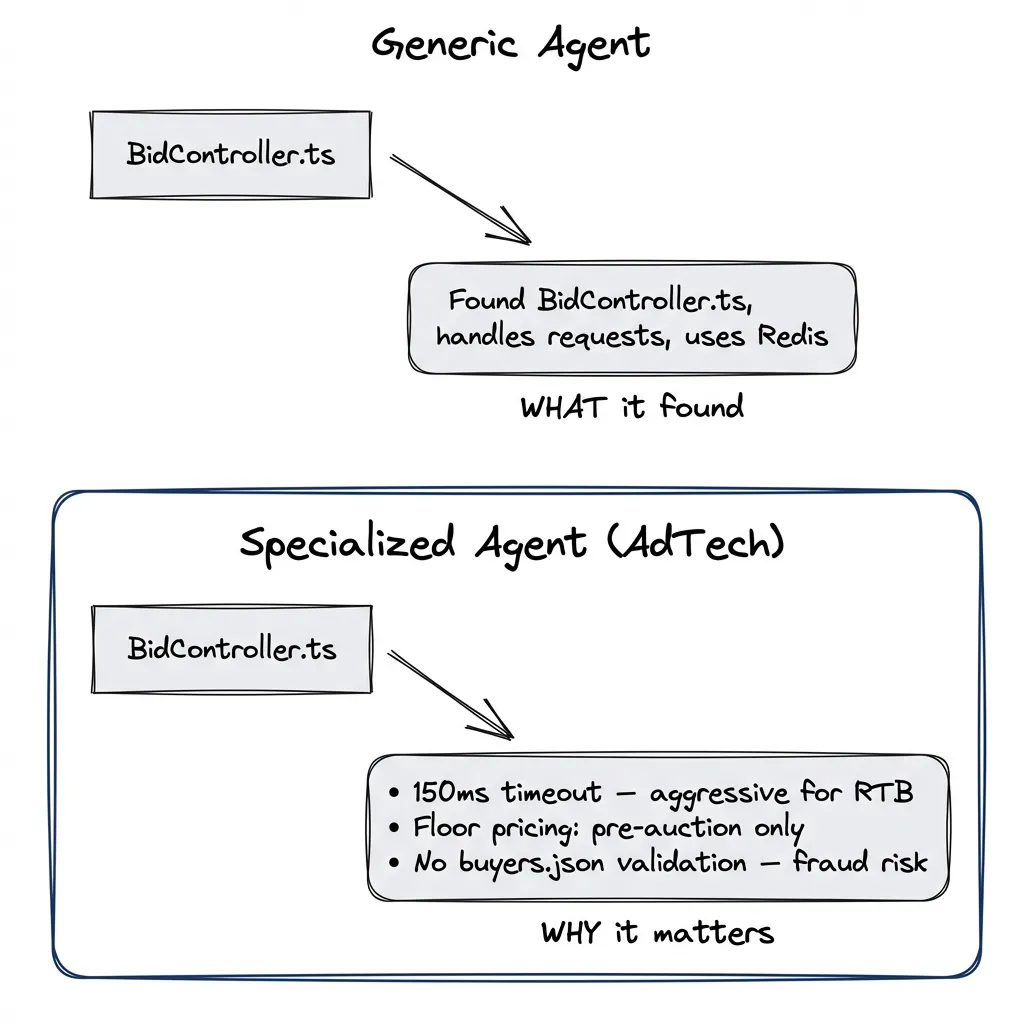

Generic agents explore generically. Specialized agents know what to look for. A “security reviewer” hunts differently than a “performance analyzer.” The prompt defines the lens.

A note on agent design: The skills post argues for action-based skills over persona-based ones — “review code for X” rather than “you are an expert in X.” The same principle applies to agents. The example below uses a persona for illustration, but in practice, focus your agent prompts on specific actions and outputs rather than role-playing.

Example: AdTech Analysis

Problem: Analyze a codebase for programmatic advertising implementation.

Generic agent reads code and reports: “Found BidController.ts, appears to handle incoming requests, uses Redis for caching.”

Specialized agent asks different questions: Where’s the bid request handling? RTB timeouts? Supply-side vs demand-side flows?

---

name: adtech-analyzer

description: "Analyze programmatic advertising implementations. Use for RTB, DSP/SSP, and ad serving architecture."

tools: Read, Grep, Glob

model: opus

---

Analyze codebases for programmatic advertising patterns.

When analyzing, look for:

- Bid request construction and validation

- Timeout handling (RTB has strict latency requirements — typically <100ms)

- Auction logic and winner determination

- Revenue tracking and discrepancy detection

- Supply chain transparency (sellers.json, ads.txt)

Output format:

- Architecture: [how bid flow is structured]

- Latency risks: [timeout issues, blocking calls]

- Compliance gaps: [missing validations, transparency issues]

- Recommendations: [specific improvements]Same codebase, different output: “Bid controller has 150ms timeout — aggressive for RTB. Floor pricing logic is pre-auction only (missing dynamic floors). No bid validation against buyers.json — fraud risk.”

The specialized agent knows what to look for. That’s what you’re encoding — not a persona, but a checklist of domain-specific concerns.

Creating Custom Sub-Agents

Use the /agents command to create and manage agents. It walks you through the setup and stores the definition in the right place.

/agents

→ Create new agent

→ Project-level (for this codebase) or User-level (all projects)

→ Generate with Claude or write manuallyYou can generate the initial definition however you like — describe what you need, paste an existing prompt — and Claude will help structure it properly.

Agent files end up in .claude/agents/ (project) or ~/.claude/agents/ (user). YAML frontmatter for configuration, markdown body for the instructions.

---

name: code-explorer

description: "Deep codebase analysis. Use for understanding unfamiliar code before implementing."

tools: Read, Grep, Glob # Restrict tool access

disallowedTools: Write, Edit # Explicitly deny tools

model: opus # opus for exploration, haiku for quick lookups

permissionMode: default # Permission handling

---

Analyze codebases to extract architectural patterns and implementation details.

When given a codebase area to explore:

1. Map the file structure and dependencies

2. Identify patterns and conventions

3. Note deviations from expected patterns

4. Summarize findings in actionable format

Output format:

- Key files: [list with one-line descriptions]

- Patterns: [what conventions does this code follow]

- Gotchas: [non-obvious behaviors, potential issues]

- Recommendations: [for implementation work that will follow]Model choice: Use Opus for exploration tasks where depth matters. Haiku for quick lookups where speed matters more than thoroughness.

Spawning:

Task(

subagent_type="code-explorer",

prompt="Explore how the payment processing module handles refunds. I need to implement partial refunds next.",

description="Explore refund handling"

)The Task tool requires three parameters:

subagent_type: matches the agent’s name fieldprompt: the actual taskdescription: 3-5 word summary

Optional: run_in_background: true for async execution while you continue working.

Testing your agent: run it, check the output, refine the prompt. Iteration is normal — most agents need a few rounds before they produce useful output consistently. Check working agents into your repo, share with your team.

Agent vs Skill vs Command:

- Agent: Autonomous investigation, isolated context, returns conclusions

- Skill: Expertise loaded into current context, no isolation

- Command: Repeatable workflow in current context, no isolation

Agents isolate. Skills and commands stay in your context.

Multi-Agent Coordination

Parallel exploration: Spawn multiple sub-agents to research different codebase areas simultaneously. Each returns findings. Main agent synthesizes.

Parallel review: Verification works well with parallel agents. Extract every claim from your work, spawn agents to find supporting and contradictory evidence in the codebase, surface mistakes. Feed corrections back to an exploration agent, run QC again. Review manually, direct it. The loop continues until the work is solid.

Implementer + reviewer: One agent builds, another evaluates. The QC validator pattern from the previous post works exactly this way — fresh context ensures no implementation bias.

Refactoring comparison: Ask different agents to model how a refactoring would look using different approaches. Compare the outputs. See which direction makes more sense before committing to one.

Example flow:

- Main agent plans implementation

- Sub-agent A explores auth subsystem

- Sub-agent B explores database schema

- Results merge, implementation proceeds with full picture

- Sub-agent C reviews completed work

- Sub-agent D verifies claims against codebase

What we’re not covering here:

- True multi-agent orchestration

- Agent communication beyond task/result

- Persistent agent teams

Current state: sub-agents are stateless function calls. You dispatch, you receive. Coordination happens in the main agent. For tracking multi-agent work across sessions, beads provides the orchestration layer — tasks with dependencies that persist.

The Catch

When sub-agents don’t help:

Tightly coupled work: If investigation and implementation are interleaved — read a file, make a small change, read another file, adjust — the back-and-forth kills the isolation benefit. Sub-agents work best for self-contained tasks.

Iterative refinement: If you need to keep asking follow-up questions based on answers, you’re better off staying inline. Each sub-agent invocation starts fresh (unless you resume it, but that adds complexity).

Overhead vs benefit: Spawning a sub-agent has cost — prompt setup, context transfer, result parsing. Reading one config file? Just read it inline. The isolation benefit has to exceed the overhead.

Nesting limitation: Subagents can’t spawn other subagents. This is an architectural decision from the Claude Code team. You can prototype multi-agent workflows, but you can’t execute truly long-running multi-agent solutions where agents spawn agents. All coordination must flow through the main conversation. This limits how far you can push autonomous orchestration — you can get partway there, but the main agent remains the hub.

Sub-agents aren’t magic. They run the same models. They don’t have special capabilities. The benefit is context isolation and fresh perspective. That’s it.

The Shift

Without sub-agents: every investigation pollutes working context.

With sub-agents: exploration stays isolated. Conclusions flow back. Main context stays clean for the actual work.

Start simple: next time you need to explore before implementing, spawn a sub-agent. Use the built-in Explore type. See what comes back.

Sixth in a series on agentic development. Previously: Stop Using Claude Code Like a Copilot, MCP Setup, Plugins, Verification Patterns, and Beads for Multi-Session Tasks. Next: putting all five pillars together.