Workflows, Not Personas

This is Part 2 of a series on building AI skills that actually work. Part 1 diagnosed why most skills fail. This part covers the methodology: how to build skills that encode developer behavior, not library descriptions.

Part 1 was the diagnosis. System prompts in a trench coat. Documentation dumps. Router collapse.

Now the methodology.

The core thesis: stop teaching agents what a library is. Teach them what a developer does.

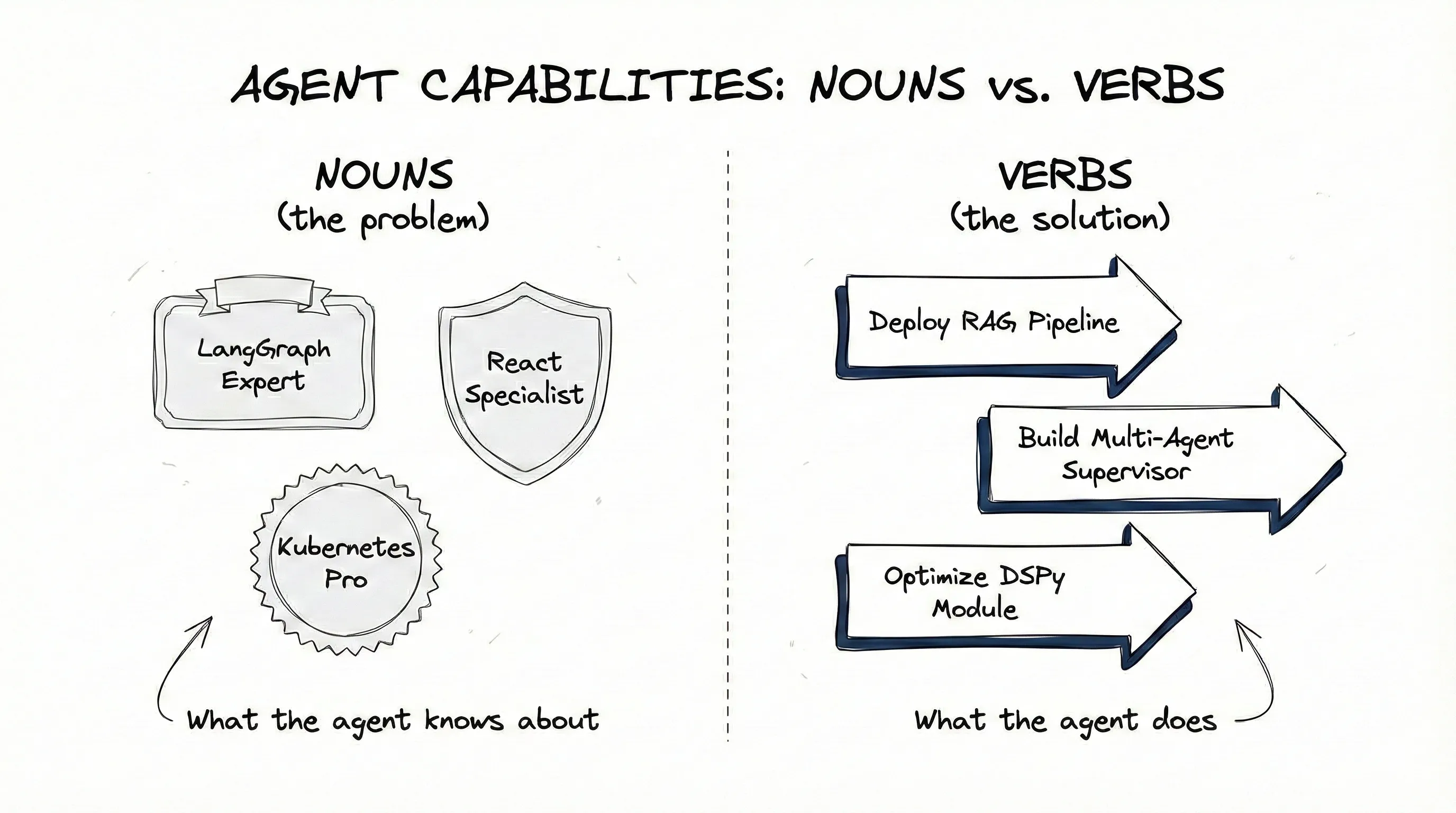

Nouns vs. Verbs

Most skill authors think in nouns. They create skills like “LangGraph Expert” or “React Specialist” or “Kubernetes Pro.” Categories. They describe what the agent should know about.

I think in verbs. My skills are named things like “Deploy RAG Pipeline” or “Build Multi-Agent Supervisor” or “Optimize DSPy Module.” Actions. They describe what the agent should do.

The structural difference matters.

A noun-based skill says: “You understand StateGraph. You know about nodes, edges, and conditional routing.” The agent reads this, feels confident, and proceeds to use StateGraph incorrectly. Knowing about something is not the same as knowing how to use it.

A verb-based skill says: “When building a multi-agent supervisor, first define the shared state schema. Then create worker agents with distinct responsibilities. Then implement the routing function that dispatches to workers. At each step, verify the state transitions.” The agent follows the procedure.

There’s another problem with noun-based skills: they don’t compose.

A real project uses multiple skills. Three, five, ten. If each one declares “You are a LangGraph Expert” and “You are a React Specialist” and “You are a Kubernetes Pro” … what is the agent supposed to be? A hydra with five heads? A case of multiple personality disorder?

This isn’t hypothetical. Conflicting identity instructions degrade performance. The agent doesn’t know which “persona” to prioritize. It hedges. It hallucinates compromises. The instructions fight each other.

Verb-based skills don’t have this problem. “Deploy RAG Pipeline” and “Build Multi-Agent Supervisor” aren’t identities. They’re procedures. An agent can follow multiple procedures without an existential crisis.

My LangGraph skills cover 21 use cases: state management, conditional routing, tool calling, RAG pipelines, multi-agent coordination, memory persistence, streaming execution. Each one is a verb. A procedure the agent can execute.

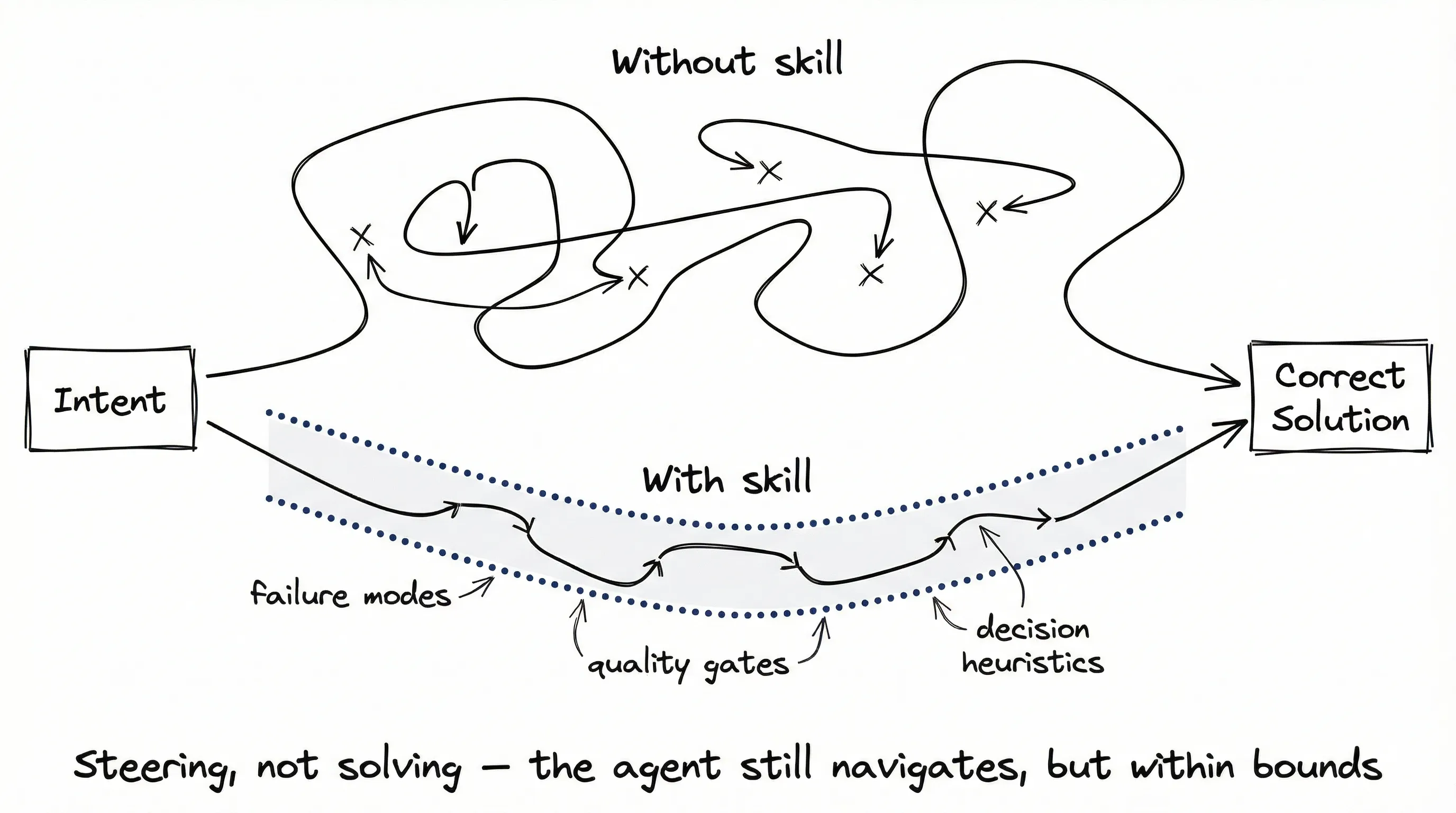

Skills as Steering, Not Solutions

A skill is not a complete solution. Can’t be. If you could fully specify every use case, you wouldn’t need an agent. You’d write a script.

The point is to steer the agent toward the right solution faster than it would find on its own. A nudge, not a replacement for judgment.

Think about what Claude already knows. It has the documentation. It can use tools like context7 or Ref.tools to look up current API references. It knows the basics of most popular libraries. If your skill just restates what’s in the docs, you’ve added tokens without adding value.

The question to ask: Will this help the agent reach the correct solution faster?

A skill that says “use Pydantic for state schemas” adds nothing. Claude already knows about Pydantic. A skill that says “when you see nested dicts in LangGraph state, that’s a code smell. Flatten them or use proper models. Here’s why the checkpoint serializer breaks otherwise” … that’s steering. It encodes a lesson the agent would otherwise learn the hard way.

The best skills encode:

- Non-obvious patterns: Things that work but aren’t in the getting-started guide

- Failure modes: What breaks and why

- Decision heuristics: When to choose option A over option B

- Quality gates: Checkpoints that catch mistakes before they compound

None of these are “the answer.” Guardrails that increase the probability of a good outcome.

When I evaluate whether something belongs in a skill, I ask: would a senior developer who knows this library well still benefit from this reminder? If yes, it’s steering. If no, the agent can look it up.

The Cookbook Methodology

I do not scrape the documentation. The docs tell you what methods exist. They don’t tell you how practitioners combine those methods to solve real problems.

So I go to the cookbooks. Find repositories where people have collected recipes. Clone them locally. Make them accessible to a Claude Code agent. Then write prompts to explore the repository in depth and surface developer patterns that could become skills.

The version doesn’t matter much. You’re looking for use cases and patterns, not API specifics. A cookbook from an older version of LangChain still shows you what developers are trying to accomplish (which means the patterns transfer even when the API details need verification later).

For LangGraph, I found several cookbook repositories from different authors. Had agents analyze what patterns show up repeatedly. What are people actually building? What order do they initialize things? What failure modes do the examples work around? The agents surfaced candidate patterns. I evaluated which ones were good skills.

The output is not a single skill. It’s a plugin of disjoint skills. 21 skills for LangGraph, each covering a distinct use case: state management, conditional routing, tool calling, RAG pipelines, multi-agent coordination. No overlap.

The output is not a “LangGraph Skill.” It’s a “LangGraph Developer Skill.” One describes the library. The other describes how a competent developer uses the library to ship working code.

The catch: agents hallucinate. They’ll confidently describe an API that doesn’t exist. Guardrails are non-negotiable.

I built two meta-skills for this: skill-qa-audit and skill-perfection. The QA skill verifies every code example against current documentation. Every import statement. Every API call. The perfection skill fixes issues in a single pass. Both run repeatedly until all examples are concise and grounded in actual docs from the latest version.

Same process for DSPy. Started from their tutorials and recipes. Had agents extract patterns for optimizers, RAG pipelines, signature design, evaluation suites. Then ran QA to verify everything against DSPy 3.1.2 docs. The result? 14 disjoint skills across six categories, all verified.

You can automate the discovery. You can automate the QA. You cannot automate the judgment about what makes a good skill. That’s still on you.

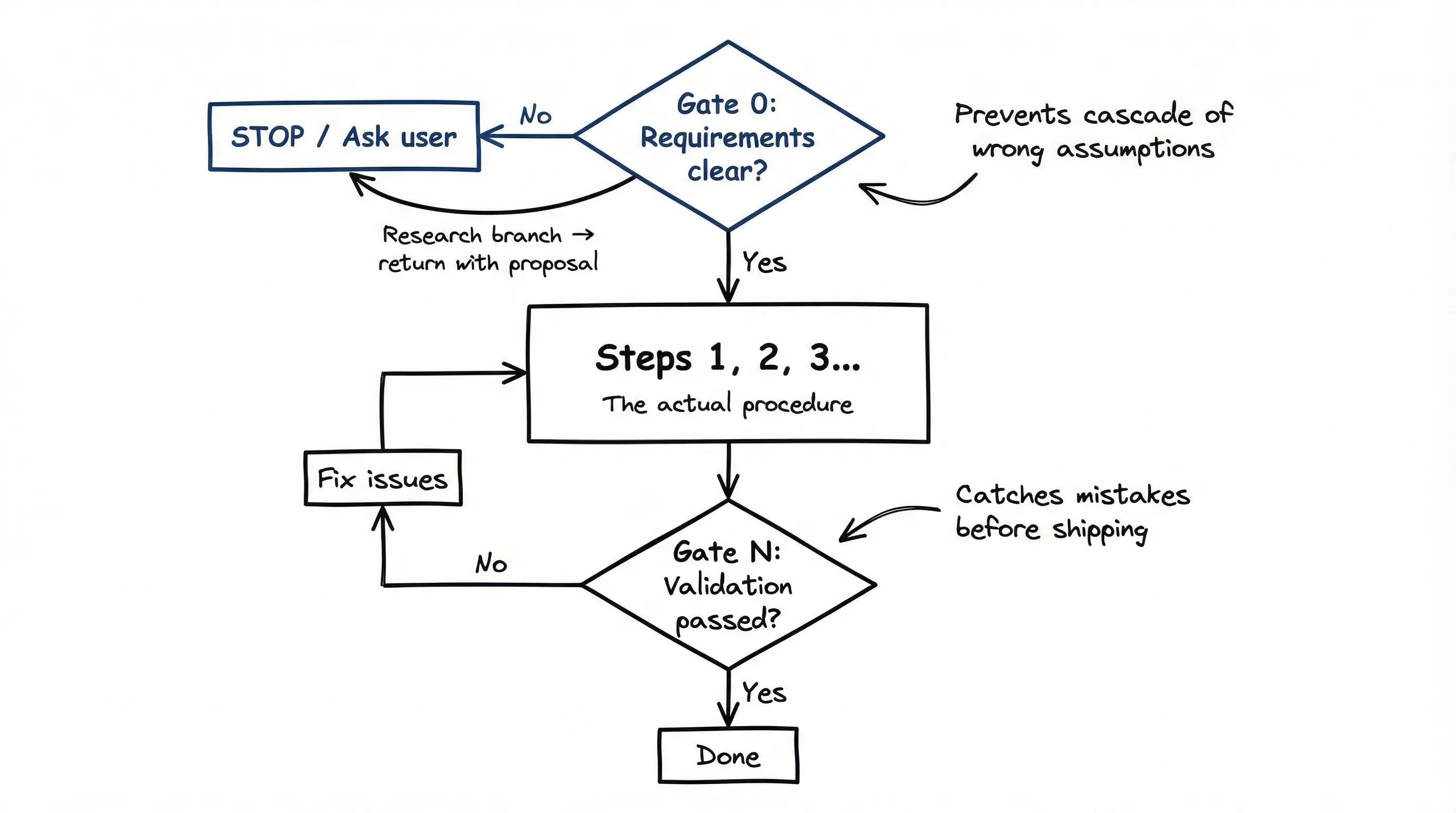

Skills as Protocols

Part 1 introduced the TDD example. Let me show the pattern more broadly.

A protocol has gates. Gates are points where the agent must stop and verify something before continuing. They prevent the cascade of errors that happens when an agent makes a wrong assumption early and compounds it for twenty steps.

Example 1: State Management (LangGraph)

Here’s how my state management skill structures the workflow:

## State Design Protocol

### Gate 0: Requirements Check

Before defining any state:

- What data flows between nodes?

- What needs to persist across graph execution?

- If unclear → STOP. Ask user to clarify data requirements.

### Step 1: Define State Schema

- Use Pydantic models (LangGraph supports both TypedDict and Pydantic; I prefer Pydantic for consistency across frameworks — DSPy, Temporal, FastAPI all use Pydantic, so one pattern everywhere)

- Store models directly, no .model_dump()

- Keep state flat when possible

### Step 2: Annotated Fields for Aggregation

- Messages that accumulate → use Annotated[list, add_messages]

- Counters that increment → use Annotated[int, operator.add]

### Gate 1: Validation

- Run `make check-langgraph` to detect violations

- Verify no dict serialization where Pydantic should be usedThe skill doesn’t just describe what StateGraph is. It tells the agent how to think about state design. Check requirements first. Use specific patterns. Validate before proceeding.

Example 2: RAG Pipeline (DSPy)

Same structure, different domain:

## RAG Pipeline Protocol

### Gate 0: Data Check

- Is the corpus accessible?

- What embedding model? (OpenAI, local, etc.)

- If corpus format unclear → STOP. Clarify with user.

### Step 1: Define Retriever

- Configure chunk size based on model context window

- Set k (number of retrieved passages) based on use case

### Step 2: Define Signature

- Input: query (str)

- Output: answer (str) with citations

### Step 3: Compose Pipeline

- retriever → context augmentation → generation

### Gate 1: Evaluation

- Run against test queries

- Check retrieval precision before tuning generationThe agent doesn’t need to understand RAG theory. Follow the steps. Check the gates.

The Gate Pattern

Every good skill has this structure:

- Gate 0: Requirements check. If ambiguous, stop and ask. If documentation is missing, branch to a research workflow before continuing.

- Steps: The actual procedure with specific instructions.

- Gate N: Validation before declaring done.

When the agent stops at Gate 0 and requirements are missing, it doesn’t just wait. It can branch to research: check the codebase for existing patterns, review related tests, look at similar implementations. Then return with a proposal for the user to approve.

Quality Gates Beyond Formatting

Part 1 mentioned quality gates. Let me be specific about what that means. (For how these gates integrate into a complete development workflow, see Verification Patterns.)

A quality gate is not just black or prettier. Modern linters do much more.

For Python, I use Ruff. Here’s what it actually checks:

[tool.ruff.lint]

select = [

"E", "W", # pycodestyle (style)

"F", # pyflakes (errors)

"I", # isort (imports)

"B", # flake8-bugbear (common bugs)

"PLR", # Pylint Refactor (God Objects, magic numbers)

"C90", # McCabe complexity

"ERA", # commented-out code

]

[tool.ruff.lint.mccabe]

max-complexity = 10

[tool.ruff.lint.pylint]

max-args = 5

max-branches = 12

max-statements = 50This catches:

- Code complexity (functions with >10 cyclomatic complexity)

- God objects (classes with too many methods)

- Magic numbers (unexplained constants)

- Anti-patterns specific to Python

- Dead code (commented-out blocks)

The quality gate is: format, lint with these rules, type check, run tests. All must pass.

When I write a skill that includes a quality gate, I specify the actual command: make quality which runs ruff format && ruff check --fix && mypy src/ && pytest. Not “run the linter.” The specific command.

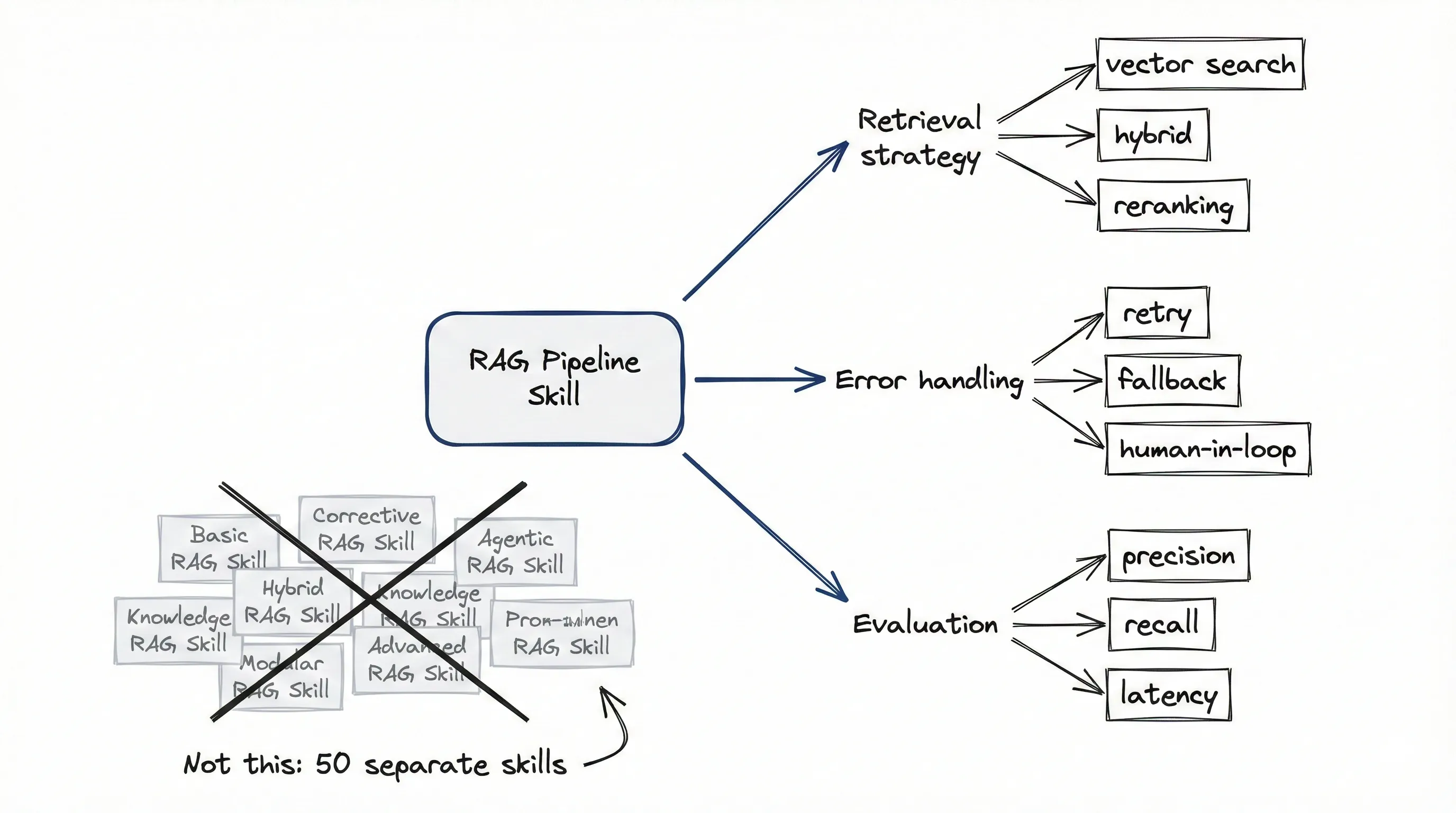

Parametric Patterns

Part 1 mentioned the abstraction ladder. The key insight: examples are not the reusable unit.

When I built my LangGraph skills, I didn’t create separate skills for “basic RAG” and “corrective RAG” and “agentic RAG.” One RAG family skill with parameters:

- Retrieval strategy: vector search, hybrid, or reranking

- Error handling: retry, fallback, human-in-the-loop

- Evaluation: precision-focused, recall-focused, latency-constrained

The skill defines the family, the parameters, and the decision points. The agent instantiates the specific variant based on requirements.

Same with multi-agent patterns. One skill covers supervisor, hierarchical, and collaborative topologies. The parameters determine which topology. The invariants (clear state ownership, explicit handoffs) apply to all of them.

This solves combinatorial explosion. You don’t need 50 skills for 50 variants. One skill per pattern family with enough structure for the agent to derive variants.

Boilerplates Are the Bedrock

A workflow is never truly generic.

A state management workflow depends on your LangGraph version. Your Pydantic configuration. Your checkpoint backend. A workflow written for in-memory checkpoints won’t work for Postgres persistence … not without modification.

This is why I organize skills in a given project around boilerplates.

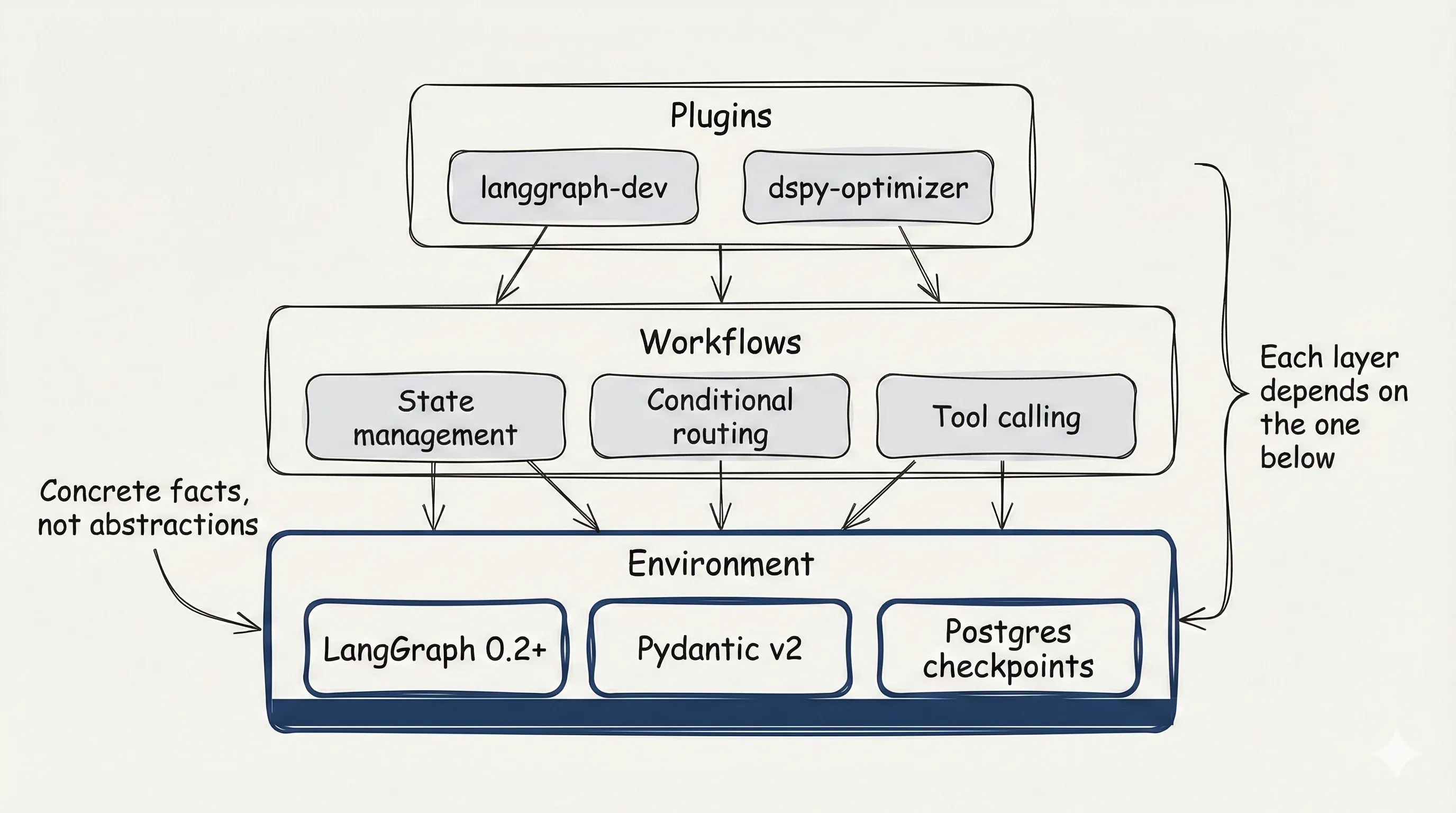

A boilerplate is: Environment + Workflows + Plugins that workflows refer to.

The environment defines concrete facts. LangGraph version. Checkpoint backend. State serialization approach. The workflows reference these specifics. “Configure checkpointing” means something because the environment defined which backend.

My LangGraph plugin assumes LangGraph 0.2+, Pydantic v2, and specific patterns for state management. Different versions? Different boilerplate.

A “universal state management skill” is fiction. The first time it tries to store a Pydantic model, it won’t know if the version supports native serialization.

The boilerplate is the onboarding document. The skill is the developer. One without the other doesn’t work.

From Persona to Protocol

The shift from personas to protocols changes how you think about agent design.

A persona asks: “What should the agent be?” Expert. Careful. Thorough. Aspirations.

A protocol asks: “What should the agent do, in what order, with what checks?” The answer is a procedure. Step 1, check requirements. Step 2, execute with specific commands. Step 3, validate before proceeding. Step 4, if failure, branch to appropriate recovery.

The methodology applies regardless of domain:

- LangGraph state management: Check data requirements → Define schema → Validate with linter

- DSPy optimization: Check baseline metrics → Select optimizer → Run with constraints → Evaluate improvement

- RAG pipeline: Check corpus → Configure retriever → Compose chain → Evaluate retrieval before tuning generation

Different domains. Same structure. Gates, steps, validation.

I don’t care if my agent “feels like” a LangGraph expert. I care if it follows the state management protocol correctly.

Part 3 covers architecture: how to organize skills, manage entropy as your system grows, and prevent the context pollution that kills agentic systems. Because even good skills become a mess when you have enough of them.