Why 95% of Claude Code Skills Are Useless, and What Actually Works

I believe in autonomous agentic coding. Agents that work independently with good guardrails, like any competent engineer. When I explored how people organize agent knowledge, I was disappointed. Skills — reusable across agents, unlike agent definitions — seemed like the best path forward. This series documents what I learned building them for production use.

I’ve been building agentic coding systems for the past year. Not demoing them on Twitter. Building them. Using them daily on production projects.

Almost everything trending about “AI skills” and “prompt packs” is noise. The flashy demos don’t work in practice. Those “Skill Seeker” scripts that promise to convert any documentation into a skill? Context pollution. The marketplaces full of downloadable “best practices”? Just system prompts in a trench coat.

I tried them. Improved some. They still don’t work.

This is the first in a four-part series on building Claude Code skills that actually work — what I call Agentic Engineering. I’m not talking about “prompt engineering,” which has been diluted to meaninglessness at this point. I’m talking about building systems where AI agents do useful work, reliably, on real codebases.

The diagnosis first.

The Geocities Era of AI Agent Skills

For those who weren’t online in the 90s: Geocities was a free web hosting service where anyone could create a website. The result was millions of amateur pages with blinking text, auto-playing MIDI music, and chaotic layouts. Most of it was enthusiastic garbage. But it was also where a generation learned to build for the web.

We’re in that phase with agentic coding. Everyone is building something. Most of it is garbage.

The scale of the problem is staggering. Smithery lists thousands of MCP servers. SkillHub has 7,000+ skills. The quality curation is minimal at best.

Browse any “awesome-agent-skills” repository. You’ll find hundreds of entries that look like this:

# TDD Expert

You are a senior software engineer who loves Test-Driven Development.

You always write tests before code.

You prefer clean, readable code.This is not a skill. It’s a costume.

It tells the model to feel like a TDD expert. It doesn’t tell the model how to do TDD. No procedure. No stop conditions. No quality gates. No definition of what “done” means.

The model reads this, nods enthusiastically, writes assert True == True, implements return True, and declares victory. You’ve accomplished nothing except wasting tokens.

I call this “vibe coding.” You’re hoping the model is in the right mood today. Sometimes it works. Usually it doesn’t. You have no idea why.

Research backs this up. PromptHub tested persona prompting across thousands of factual questions and found that “system prompts or personas didn’t improve performance, and sometimes had negative effects.” Personas work for creative writing. For accuracy-based tasks? Useless or harmful.

Why Documentation Dumps Kill Claude Code Skills

The second failure mode I see constantly: stuffing documentation into the context window.

I’ll tell you how I got here. When I first had the idea that skills could organize specialized knowledge, my instinct was to automate it. Build a wrapper that extracts library knowledge into skills automatically. I searched around and found Skill Seeker, which claimed to do exactly this. I was excited. Someone already solved it.

I cloned the repo. The SKILL.md structure it generated was… not good. Credit to the Skill Seeker author for the idea, but the one-shot AI enhancement approach couldn’t produce quality output. I rewrote the enhancement as an agentic process with iterative refinement. The structure improved significantly.

But then I realized the fundamental problem. Skill Seeker parses code and documentation. AST analysis. Reference extraction. It doesn’t observe how developers actually use the library. Wrong source entirely. You can’t deduce use cases from code structure. You need cookbooks, real projects, patterns of actual usage.

The tool also assumes one library equals one skill. There’s a “multi-skill” feature in development, but even that misses the point. Any significant library needs multiple disjoint skills covering different use cases, not one monolithic blob.

After a few days of experimenting… I gave up on that road. The agentic enhancement worked, but the seed information — code and reference docs — lacks the richness required to build useful skill plugins.

The underlying problem: you dump 20,000 tokens of API reference into the context. The agent now has access to every method signature, every parameter, every edge case.

But the agent doesn’t know what to do with any of it. Ingredients without a recipe. It picks a method that seems relevant, probably uses it wrong. And you’re paying for those tokens on every turn.

Worse: documentation goes stale. The moment you save that text file, it starts drifting from the actual library. Three months later, you’re teaching the agent deprecated patterns.

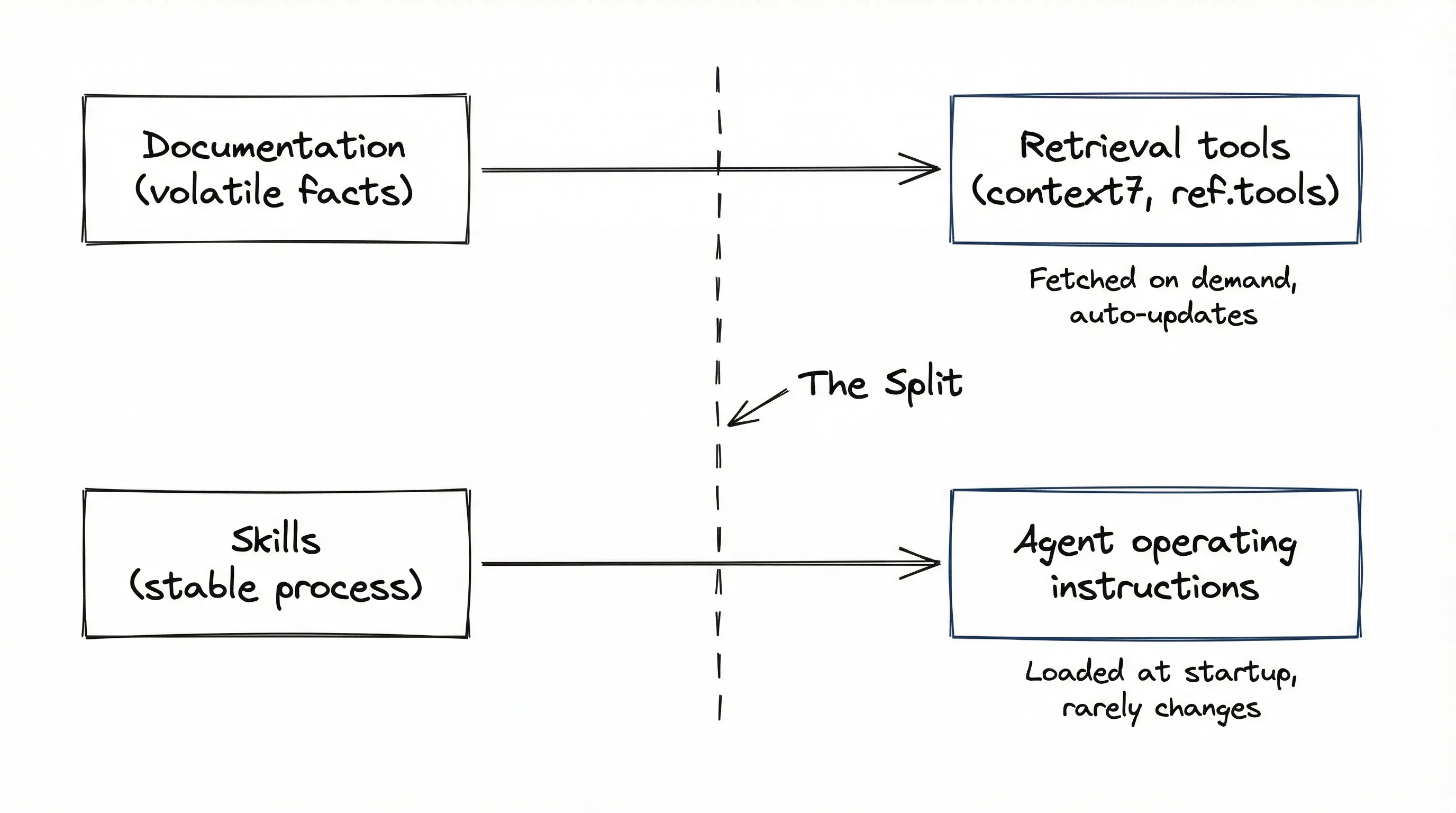

The fix is architectural. Documentation and skills serve different purposes:

- Documentation (volatile facts) -> belongs in retrieval tools

- Skills (stable process) -> belongs in the agent’s operating instructions

For documentation, use MCPs like context7 or ref.tools. These are retrieval engines designed for exactly this purpose. They fetch current, relevant slices of documentation when the agent asks. They auto-update. They don’t waste context on information the agent won’t use.

Skills should not be about what a library is. Skills should be about what a developer does.

The System Prompt Fallacy: Why Personas Don’t Work

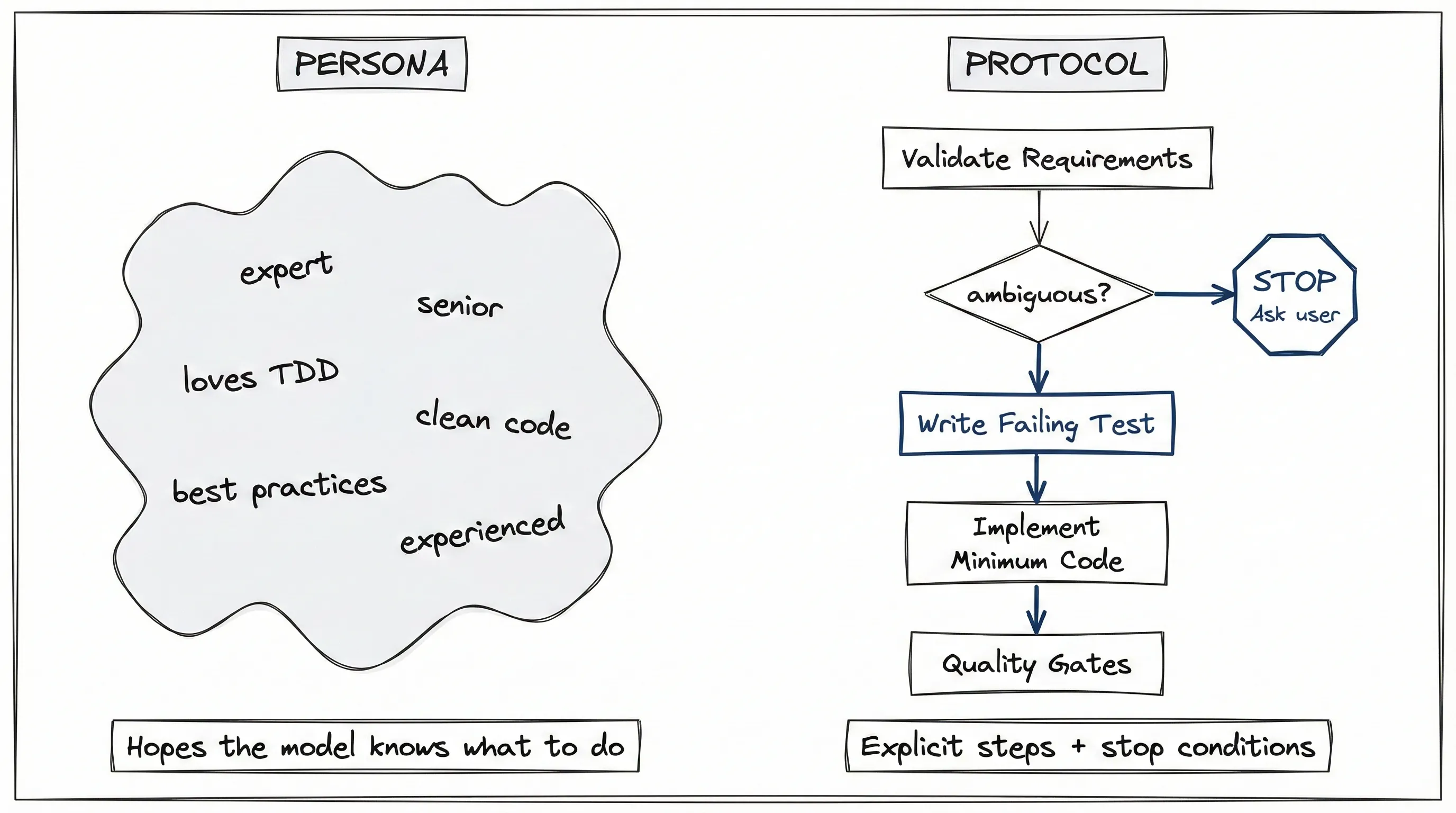

Let me show you the difference between a persona and a protocol.

A persona (useless):

You are a TDD expert. You always write tests first.

You prefer clean, well-documented code.A protocol (useful):

## TDD Workflow

### Step 1: Validate Requirements

Before writing any test:

- Check if product spec exists

- If requirements are ambiguous -> STOP. Ask user to clarify.

- Do NOT guess. Do NOT assume.

### Step 2: Write Failing Test

- Test must reference specific acceptance criterion from spec

- Run test -> verify it FAILS

- If test passes before implementation -> test is wrong

### Step 3: Implement Minimum Code

- Write ONLY enough code to pass the test

- Do NOT add features not in the spec

- Do NOT optimize prematurely

### Step 4: Quality Gates

- Run `make quality` (format, lint, typecheck, tests)

- ALL gates must pass before commit

- Green test is not done. Quality gate = done.

## The Sacred Rule

Tests are grounded in requirements, NOT implementation.

If test fails -> fix code.

If test seems wrong -> clarify requirements with user.

NEVER adjust tests to match code.The persona hopes the model knows TDD. The protocol enforces it through explicit stop conditions, verification steps, and quality gates. Obvious difference.

Notice Step 1: “If requirements are ambiguous -> STOP.” Most important line. It gives the agent permission to halt and ask questions instead of guessing. Without this, agents plow forward with assumptions, and you discover the mistake three hours later.

The “Sacred Rule” exists because I’ve watched agents do this wrong dozens of times. Test fails. Agent thinks “the test must be wrong.” Adjusts test. Test passes. Code is still broken. This rule makes explicit what should be obvious: tests define the contract.

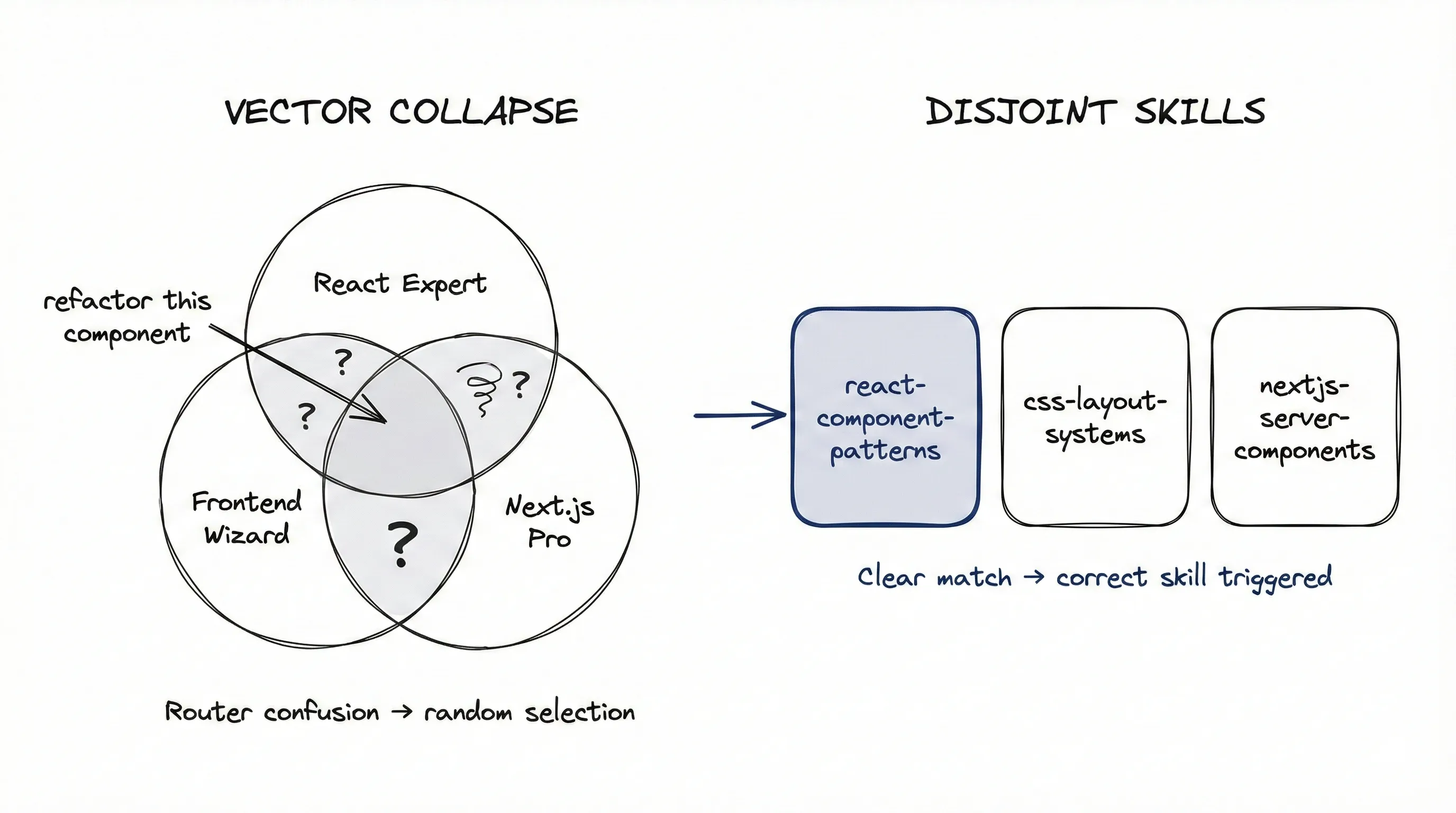

The Skill Router Bottleneck

A problem nobody talks about: skill discovery doesn’t work.

The marketing pitch sounds great. Install 50 skills, and the agent “automatically” picks the right one. In practice, if you have:

- “React Expert”

- “Frontend Wizard”

- “Next.js Pro”

…the semantic embeddings overlap almost entirely. When you ask “refactor this component,” the model sees three identical signals. It becomes indecisive, picks randomly, or ignores all of them.

I call this Vector Collapse. More overlapping skills means lower probability of the correct one being triggered.

This isn’t just intuition. Research on tool selection found that “existing retrieval methods typically match queries against coarse agent-level descriptions before routing, which obscures fine-grained tool functionality and often results in suboptimal agent selection.” Another study showed 99% token reduction and 3.2x accuracy improvement by filtering to fewer, better-matched tools.

The solution isn’t smarter routing. Discipline is:

- Disjointness: No two skills should cover the same intent

- Explicit invocation: Your workflows should call skills by name, not hope for automatic discovery

In my systems, workflows explicitly invoke Claude Code custom commands: /test-driven-development, /beads:workflow, /subagent-driven-development. The skill names become the command line. I don’t trust automatic routing. Neither should you.

What a Claude Code Skill Actually Is

So what is a useful skill?

I think the best definition is this: a skill is a reusable decision + procedure unit that transforms intent into outcome under constraints, with guardrails, failure modes, and verification steps.

Dense. Let me unpack it.

- Reusable: Works across similar situations, not just one specific case

- Decision + procedure: Includes judgment calls along with step-by-step actions

- Intent -> outcome: Takes a goal and produces a result

- Under constraints: Respects the environment (test runner, linter, git workflow)

- Guardrails: Prevents known failure modes

- Verification: Explicit checks that the skill succeeded

A concrete test: can you trace a line from every acceptance criterion in your spec to a test in your codebase? If yes, your skill is working. If no, you have gaps.

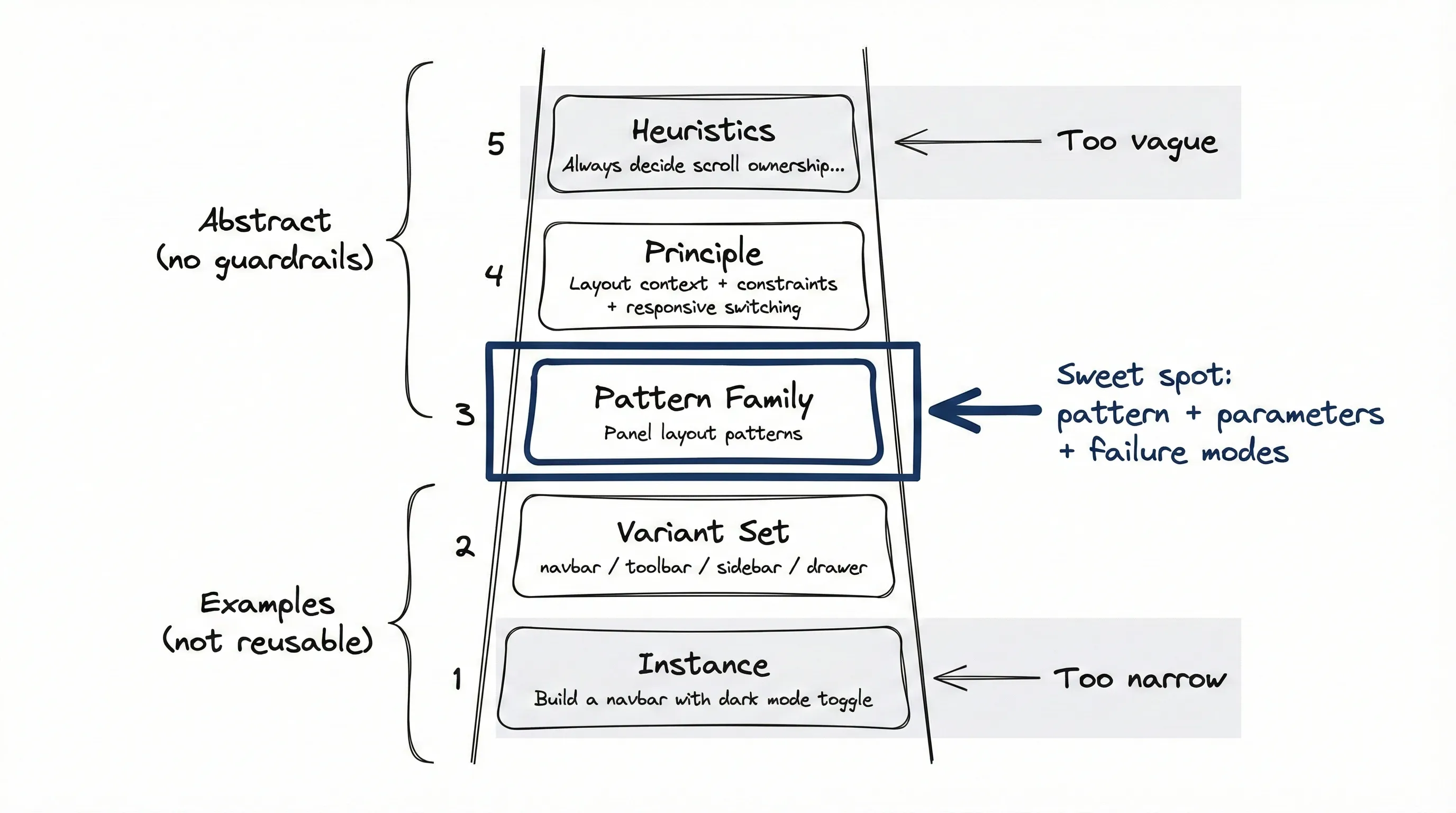

The Abstraction Ladder

One more concept.

Most “skills” are too specific or too vague. There’s an abstraction ladder that matters:

- Instance: “Build a navbar with dark mode toggle”

- Variant set: “Build navbar / toolbar / sidebar / drawer”

- Family: “Panel layout patterns”

- Principle: “Layout context + constraints + responsive switching”

- Heuristics: “Always decide scroll ownership. Apply shrink rules. Theme via tokens.”

Examples (instances) are not the reusable unit. The pattern family is, plus:

- Invariants (what must always be true)

- Parameters (what varies)

- Decision points (where choices get made)

- Failure modes (what can go wrong)

Examples are just witnesses that prove a pattern works. If your skill is an example, too narrow. If your skill is a principle without failure modes… too vague.

The sweet spot is the pattern family with explicit parameters and guardrails.

Why Most Claude Code Skills Fail: Summary

Long story short, here’s where we are:

- System prompts disguised as skills - tell the agent to be something without teaching it to do something

- Documentation dumps - flood the context with ingredients, no recipe

- Router collapse - too many overlapping skills means none of them get triggered reliably

- Wrong abstraction level - either too specific (examples) or too vague (principles without guardrails)

The fix isn’t downloading more skills. It’s engineering fewer, better ones.

Part 2 covers the methodology: how to build skills that work. Not by scraping documentation, but by mining recipes from cookbooks and real-world usage. I call the approach “Workflows, Not Personas.”