How to Engineer a Skill

This is Part 4 of a series on building Claude Code skills and custom commands that actually work. I originally went down the same road as automated skill generators — parsing code and docs. That approach failed. Use cases come from cookbooks and real usage patterns, not AST analysis. This part is the methodology I developed instead.

Part 1 diagnosed the problem. Part 2 covered the philosophy. Part 3 handled architecture.

This part is process. Step by step, how I actually build a skill.

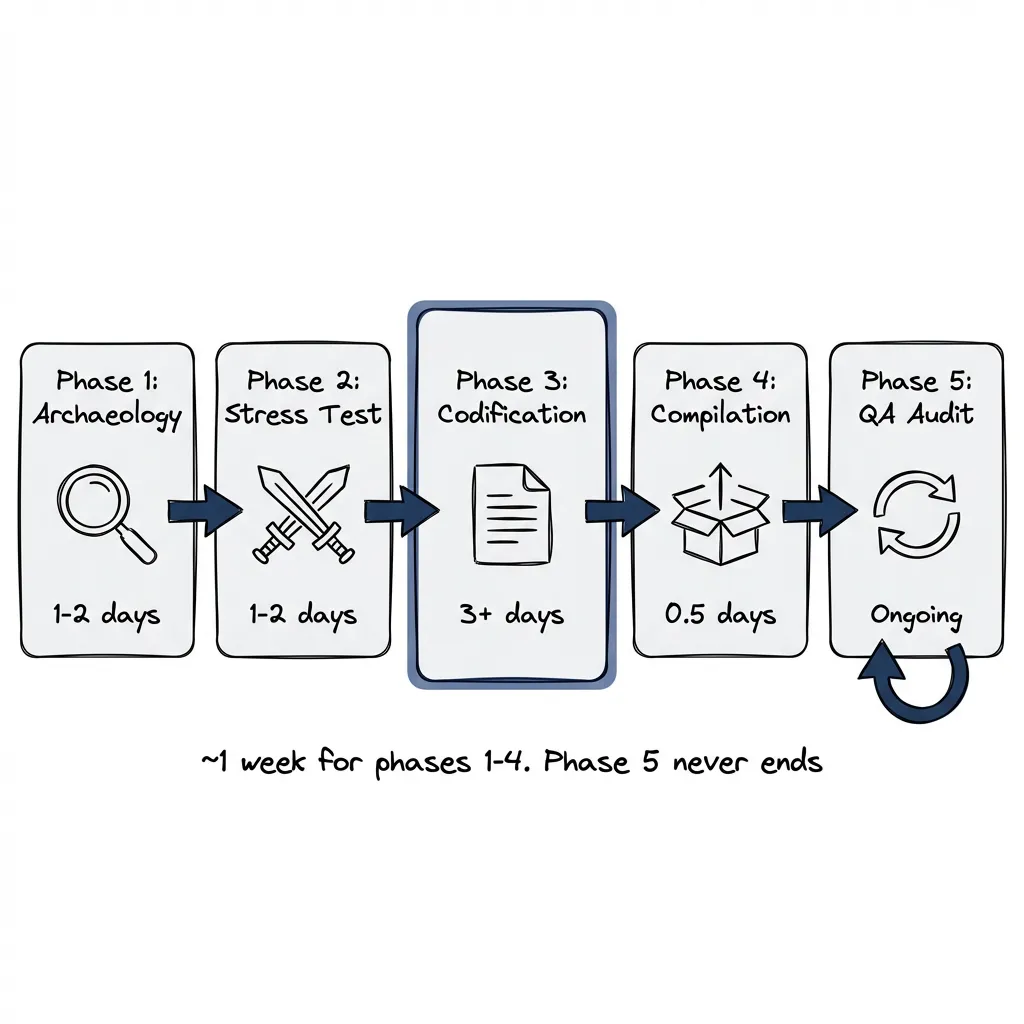

The Five Phases

- Archaeology: Find the patterns worth encoding

- Stress Test: Challenge each skill before it ships

- Codification: Structure it for Claude

- Compilation: Bundle skills into a project

- QA Audit: Verify it still works

Each phase has specific outputs. Skip one and you’ll feel it later.

Phase 1: Archaeology

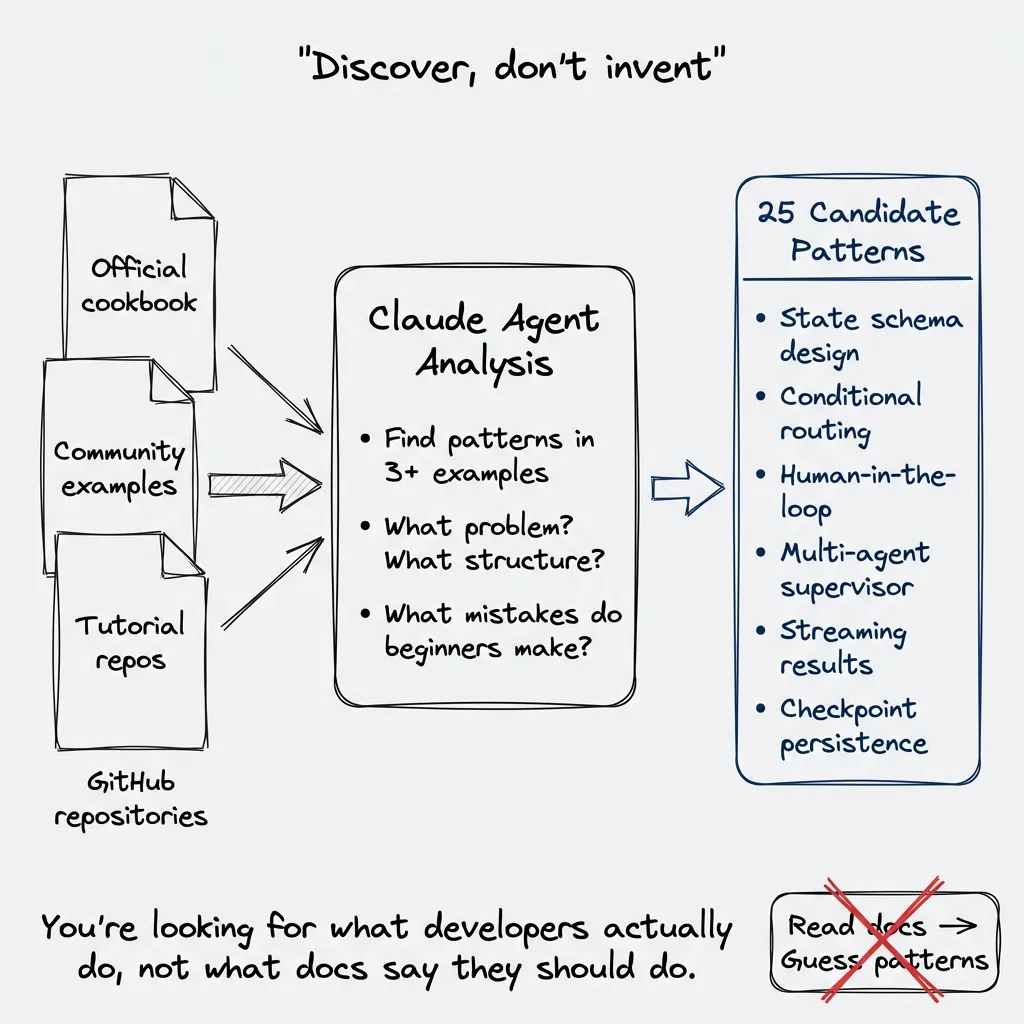

You don’t invent patterns. You discover them.

This took me a while to learn. My first instinct was to read the official docs, understand the library deeply, then write skills based on what I thought developers should do. Wrong approach. What I thought they should do and what they actually do… different things entirely.

The right question: what are people actually doing with this library? Not the docs. Not the marketing. What patterns show up repeatedly when developers solve real problems?

The Cookbook Method

Go to GitHub. Search for cookbooks, examples, tutorials. Repositories where people have collected recipes.

For LangGraph, I found several cookbook repositories from different authors. Some official examples, some community collections. Clone them. Make them accessible to a Claude Code agent.

Then write prompts to explore. Not “summarize these files.” Something like:

Analyze this cookbook repository. Find patterns that appear in 3+ examples.

For each pattern:

- What problem does it solve?

- What's the core structure?

- What variations exist?

- What mistakes do beginners make?The agent reads through hundreds of files. Surfaces what repeats. You’re looking for the 80/20: which patterns cover most use cases?

What You’re Finding

The output isn’t documentation. It’s use cases.

For LangGraph, the patterns that emerged:

- State schema design with Pydantic

- Conditional routing based on state

- Human-in-the-loop interruption

- Multi-agent supervisor coordination

- Streaming partial results

- Strategies for checkpoint persistence

Each of these is a distinct skill. Not “LangGraph fundamentals.” Not “LangGraph best practices.” Specific use cases with specific patterns.

Version Tolerance

The cookbook might be from an older version. Fine. You’re looking for what developers try to accomplish, not API specifics.

A LangChain cookbook from 2023 still shows you the problems people solve with chains. The patterns transfer. The API details get verified later during QA.

Output of Phase 1

A list of candidate skills. Each one:

- Named after the use case it solves

- Has 2-3 concrete examples from the cookbook

- Covers a distinct problem without overlapping with others

For LangGraph, I started with 25 candidates. Some got merged. Some got cut. But the archaeology gave me the raw material.

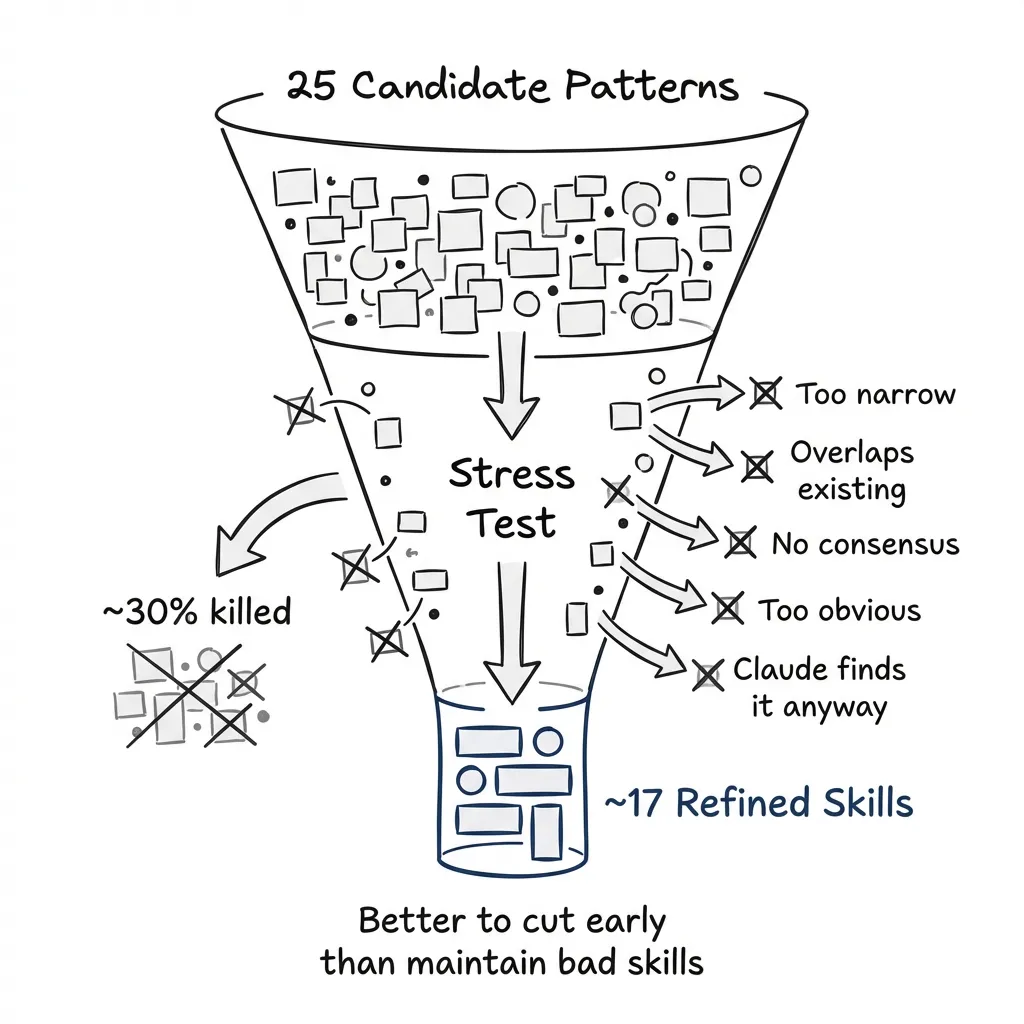

Phase 2: Stress Test

Before writing SKILL.md, challenge the pattern.

The Devil’s Advocate Prompt

I use Claude as a critic. Not a cheerleader. The prompt:

I'm building a skill for [use case]. Here's my current understanding of the pattern:

[Pattern description]

Challenge this:

1. What edge cases would break this pattern?

2. What's the most common mistake developers make?

3. When should someone NOT use this approach?

4. What's missing from my description?

5. What would a senior engineer criticize about this pattern?The responses surface gaps. Things I assumed but didn’t state. Edge cases I didn’t consider.

Research Branch

Sometimes the stress test reveals knowledge gaps. The pattern mentions a concept I don’t fully understand. Or there’s a better approach I hadn’t considered.

This triggers a research branch. Go back to cookbooks. Search for the specific edge case. Find examples of the anti-pattern. Understand why it fails.

The stress test isn’t pass/fail. It’s a feedback loop that improves the pattern before encoding.

When to Kill a Skill

Some patterns don’t survive stress testing.

Signs a skill isn’t worth building:

- The pattern only applies in narrow circumstances

- Too much overlap with an existing skill

- The “best practice” is actually contested (no consensus)

- The pattern is so simple it doesn’t need encoding

- Claude would reach this conclusion anyway with a web search or documentation lookup

That last one matters most. A skill exists to steer the agent faster than it would navigate on its own. If the pattern is obvious, if it’s clearly stated in the getting-started guide, if Claude would find it with context7 or Ref.tools, you’re adding tokens without adding value.

The test: imagine Claude has full documentation access. Would this skill change its behavior? If not, kill it.

I killed about 30% of my LangGraph candidates after stress testing. Better to cut early than maintain bad skills.

Output of Phase 2

Refined patterns. Each surviving skill now has:

- Clear scope (what it does, what it doesn’t)

- Known edge cases documented

- Anti-patterns identified

- Confidence that the pattern is actually useful

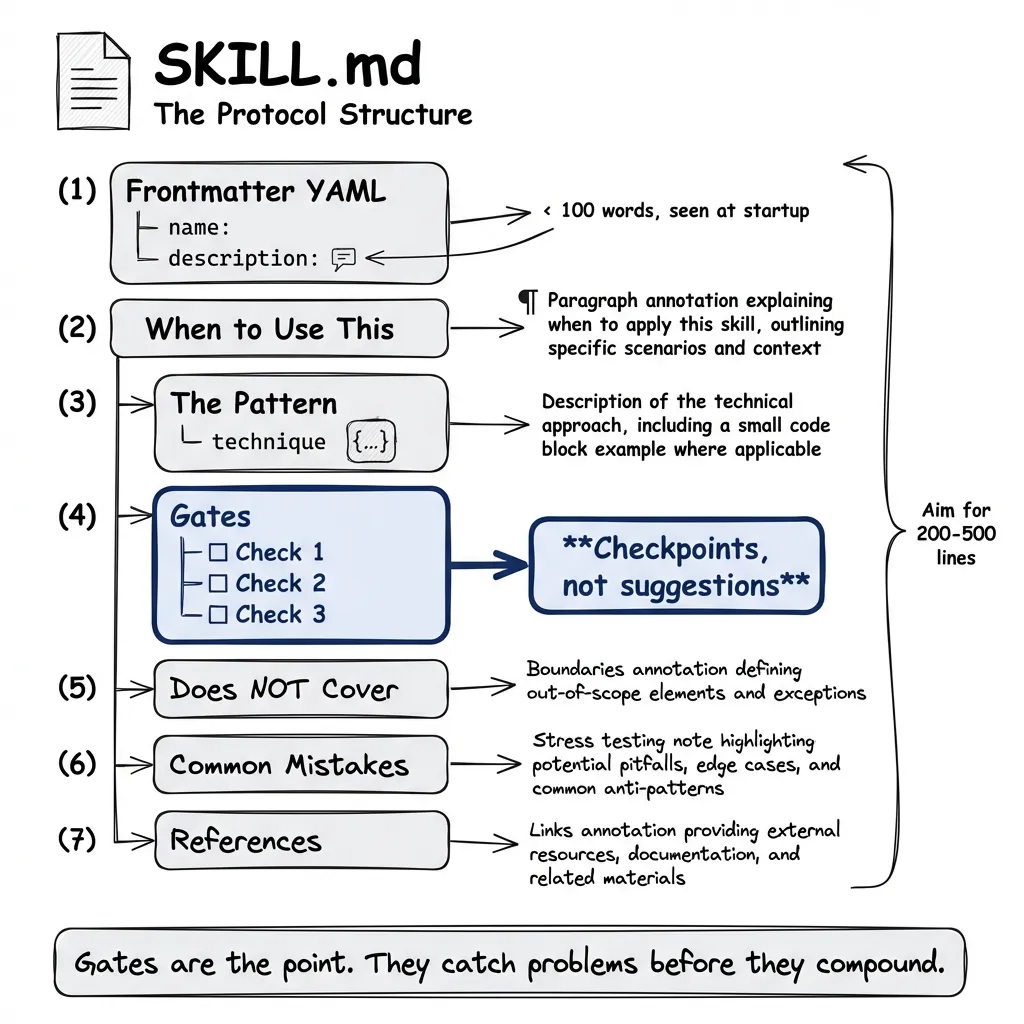

Phase 3: Codification — Writing the SKILL.md

Now write the SKILL.md.

Naming Convention

Follow the namespace:

{domain}-{subdomain}-{specific-topic}

langgraph-dev-state-management

langgraph-dev-conditional-routing

dspy-optimizer-miproThe name should be enough to guess what the skill does. No clever names. No abbreviations.

The Frontmatter

---

name: langgraph-dev-state-management

description: >

Design state schemas for LangGraph applications. Use when user asks about

"state schema", "TypedDict", "Annotated fields", "state reducers", or

"MessagesState". Does NOT cover conditional routing or checkpoint persistence.

---The description has three jobs:

- Say what the skill does

- List trigger phrases

- Say what it doesn’t do (anti-triggers)

Under 100 words. Claude sees this at startup for every skill.

The Protocol Structure

The body follows this pattern:

# [Skill Name]

## When to Use This

[One paragraph: what problem this solves]

## The Pattern

[The actual technique, with code example]

## Gates

[Quality checks before proceeding]

## Does NOT Cover

[Explicit boundaries - what triggers other skills]

## Common Mistakes

[What to avoid, based on stress testing]

## References

[Links to detailed docs if needed]Gates Are the Point

Every skill has quality gates. Not suggestions. Checkpoints.

## Gates

Before proceeding, verify:

- [ ] State schema uses Pydantic BaseModel (I prefer Pydantic over TypedDict for consistency with DSPy, Temporal, FastAPI)

- [ ] All aggregation fields use Annotated with operator.add

- [ ] No nested dicts (use flat structure or models)

- [ ] Messages field uses MessagesState base classGates catch problems before they compound. They encode the lessons from stress testing.

Code Examples

Include runnable code. Not pseudocode. Not fragments.

# Complete, runnable state schema

from typing import Annotated

from pydantic import BaseModel

from langgraph.graph import add_messages

class ConversationState(BaseModel):

messages: Annotated[list, add_messages]

current_step: str = "start"

retry_count: int = 0The example should work if you paste it. No “replace with your code” placeholders.

Line Budget

Anthropic recommends under 500 lines. I usually aim for 200-300, but honestly? I’ve gone over. If a skill needs 600 lines to be complete and well-structured, I’d rather have a complete skill than an artificially chopped one. The 500 is a guideline, not a law.

If the skill is getting long, first check: am I dumping reference material that should be in a separate file? Usually yes. Split the content. Put deep reference material in its own file. SKILL.md points to it:

## Advanced Patterns

For complex state aggregation patterns, see [references/advanced-aggregation.md](references/advanced-aggregation.md).Claude loads the reference only when needed.

Output of Phase 3

A complete skill directory:

langgraph-dev-state-management/

├── SKILL.md # Main content (under 500 lines)

├── references/

│ └── advanced.md # Deep content (loaded on demand)

└── examples/

└── complete.py # Runnable code

Phase 4: Compilation — Bundling into Claude Code Plugins

Claude Code skills live in plugins. You don’t copy-paste individual skills into projects — you enable the plugins that matter.

Plugins, Not Loose Files

A plugin bundles related skills. My LangGraph plugin has 21 skills. My DSPy plugin has 14. When you enable a plugin for a project, all its skills become available.

The decision isn’t “which skills do I copy?” It’s “which plugins does this project need?”

A typical project might enable:

- One or two framework plugins (LangGraph, DSPy)

- A workflow plugin (TDD, deployment patterns)

- Maybe a project-specific plugin for domain logic

That’s maybe 30-40 skills total. Manageable.

Why Per-Project Enablement Matters

The problem isn’t really conflict between disjoint skills. Frontend development skills don’t clash with database skills. AI pipeline skills don’t interfere with deployment patterns. If your project genuinely touches all those areas, enable all those plugins. Fine.

The real problem is attention.

Even with progressive disclosure — where Claude only loads full skill content when needed — you still see the metadata. Run /skills and you might see fifty, seventy, a hundred entries. Ninety percent of them irrelevant to what you’re actually building.

That’s not context overload for the model. It’s cognitive overload for you.

Maybe it seems fun to enable a plugin development skill “just in case.” But if you’re not building plugins in this project, why is it there? Every time you scan the skill list, you’re wading through noise.

The Conscious Decision

I advocate enabling plugins per project. Same for MCPs. Every project gets a deliberate choice: do I need this here?

my-project/

├── .claude/

│ └── settings.json # Lists enabled plugins

├── src/

└── ...When you start a new project, you make a conscious decision. LangGraph? Yes, we’re building agents. DSPy? No, not doing optimization here. Plugin development? Not in this repo.

The result: when you run /skills, you see skills that actually apply. When Claude considers which skill to invoke, the candidates are relevant. Less noise. Clearer signal.

Checking for Conflicts

Before finalizing, verify:

- No trigger overlap: Read each plugin’s skill descriptions. Any phrase that appears in two skills?

- No advice conflicts: Do any skills give contradictory guidance?

- Complete coverage: Does the set cover the project’s likely tasks?

Two skills overlap? That’s a plugin design problem. Fix it upstream.

Output of Phase 4

A project with deliberately chosen plugins. Nothing enabled “just in case.”

Phase 5: QA Audit

Skills rot. APIs change. Best practices evolve. Examples break silently.

The Meta-Skills

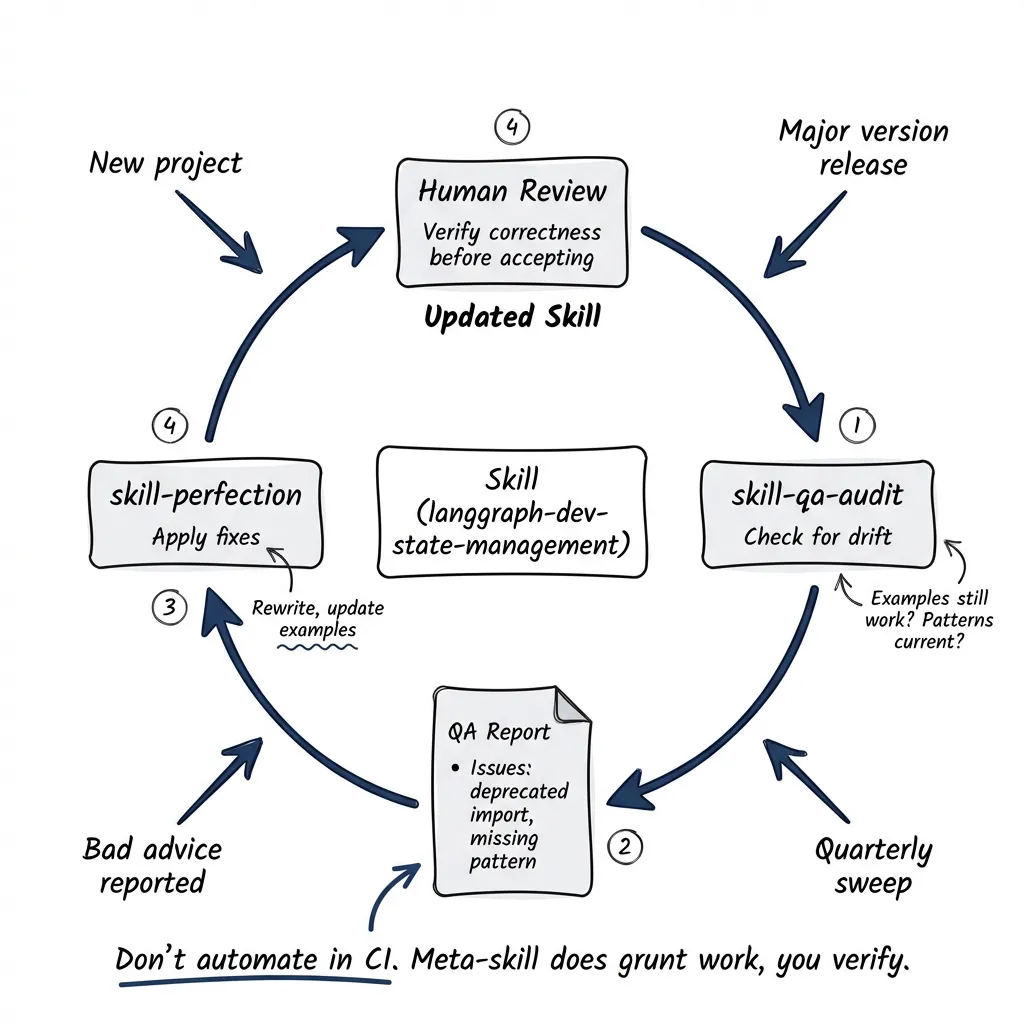

I built two meta-skills for maintenance (both available in the plugin-qa plugin):

skill-qa-audit: Evaluates an existing skill. Checks if examples still run. Identifies outdated patterns. Flags contradictions with current library docs.

skill-perfection: Improves a skill based on QA findings. Rewrites sections. Updates examples. Fixes identified issues.

Running an Audit

When I suspect drift or before adding a skill to a new project, I invoke the custom slash command:

/skill-qa-audit langgraph-dev-state-managementThe meta-skill:

- Reads the skill’s SKILL.md

- Checks examples against current library behavior

- Searches for updated patterns in recent documentation

- Reports findings with specific issues

Output looks like:

## QA Report: langgraph-dev-state-management

### Issues Found

- Example at line 47 uses deprecated `add_messages` import path

- Missing coverage of new `StateGraph` builder pattern

- Gate 3 references TypedDict but skill recommends Pydantic

### Recommendations

1. Update import to `from langgraph.graph.message import add_messages`

2. Add section on StateGraph builder

3. Remove TypedDict from gates (contradicts recommendations)Fixing Issues

If the audit surfaces problems:

/skill-perfection langgraph-dev-state-managementThis meta-skill:

- Reads the QA report

- Reads the current SKILL.md

- Applies fixes

- Outputs the updated skill

Review the changes before accepting. The meta-skill does the grunt work. You verify correctness.

When to Audit

Before adding a skill to a new project. When the library releases a major version. When someone reports that a skill gave wrong advice. And honestly, just… periodically. I try to do quarterly sweeps but I’m not always consistent about it.

Don’t automate this in CI. I thought about it. The problem: automated fixes can make things worse. A stale skill that gives outdated advice is bad. A skill that got “fixed” by an unsupervised agent and now gives confidently wrong advice? Worse. The meta-skill does the grunt work, but you review what it produces.

Output of Phase 5

Verified, up-to-date skills ready for deployment.

Building the Skill: The Full Timeline

The full cycle for a new library, roughly:

Archaeology takes a day or two. Clone cookbooks. Run analysis prompts. You’ll surface maybe 15-30 candidate patterns.

Stress test is another day or two. Challenge each pattern. Kill about 30%. Refine survivors.

Codification is the longest. Three days, maybe more if you’re thorough. Write SKILL.md for each surviving pattern. Structure properly. Include runnable examples. This is where the actual writing happens, which means it takes the most time.

Compilation is quick. Half a day. Build project pack. Check for conflicts. Deploy.

QA Audit is ongoing. Doesn’t fit in a timeline because it never ends.

The first four phases take about a week for a new library. Sometimes faster if the library is small. Sometimes longer if I’m learning the domain while building the skills. The fifth phase is just maintenance. Forever.

What You Get

A skill built this way:

- Solves a real problem (discovered, not invented)

- Has clear boundaries (stress tested)

- Includes quality gates that catch mistakes early

- Works with other skills (compiled without conflict)

- Stays current (audited periodically)

I think this is engineering, not prompting. The skill is an artifact with a lifecycle. It needs design, implementation, testing, and maintenance.

The 95% of skills that fail? They skip phases. They invent patterns instead of discovering them. No stress testing. No gates. They ship and never get audited.

Long story short: don’t skip phases.