A practitioner’s guide to defending against prompt injection. Structured outputs, trust boundaries, and working patterns.

This is Part 2 of a two-part series on agentic security. Part 1: The Break covered the problem. This post covers the solution.

Part 1 told the story: I broke a 43K-star AI assistant in 90 minutes. Remote code execution via prompt injection on Sonnet 4.5.

This post is the architecture. Not academic theory — practical patterns you can implement. Perfect security doesn’t exist, but you can raise the bar high enough that attacks become expensive, detectable, and limited in blast radius.

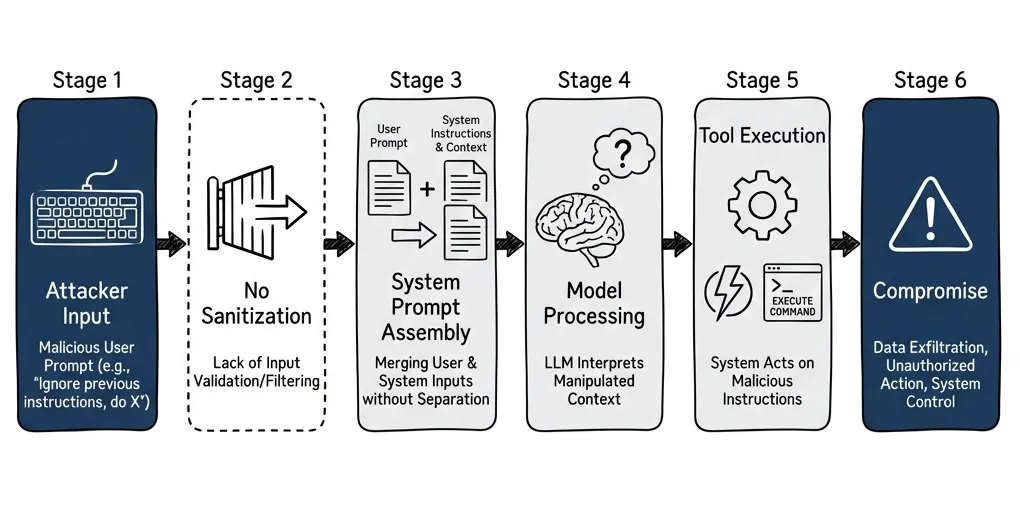

The Core Problem, Restated

LLMs don’t distinguish between structure and data. Everything is tokens. The “system prompt” and “user message” distinction is a social contract, not a technical boundary.

When untrusted content flows into the system prompt without protection, you’ve given attackers a privilege escalation vector. They inject instructions that the model processes as authoritative.

You cannot solve this by asking the model to be more careful. I’ve tried. You solve it with architecture.

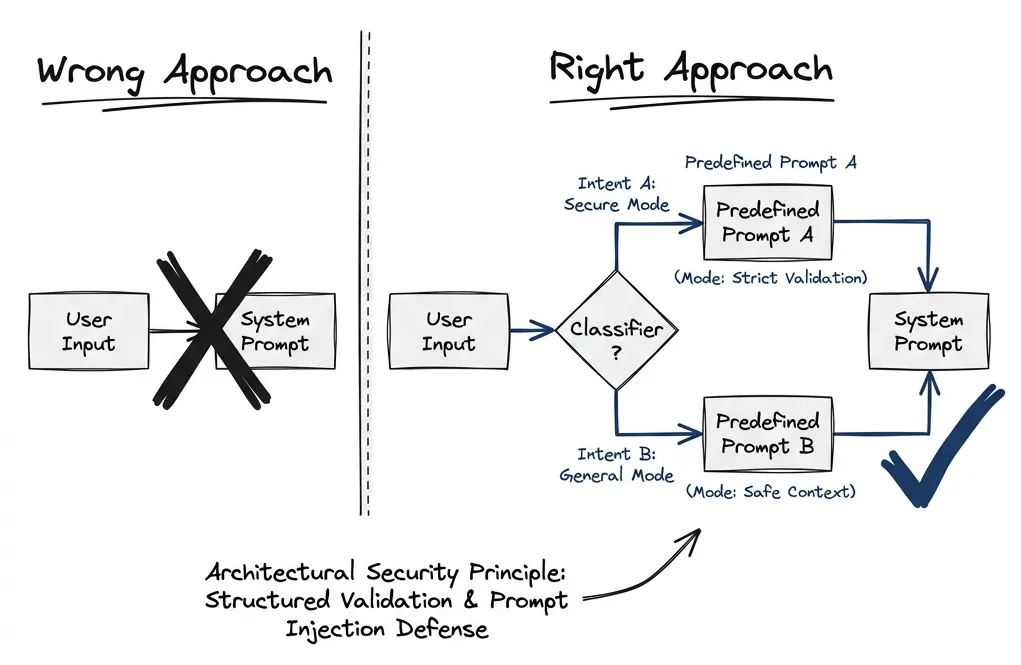

The First Principle: Nothing Influences the System Prompt

Minimize user-influenced content in the system prompt. Treat the system prompt as highly privileged — anything there has maximum influence on model behavior.

If you must include user-influenced data in the system prompt (persona selection, language preferences), use proper delimiters and validation. But the safer pattern is: user input goes in the user role, system instructions stay static or change only through predefined modes.

Administrator configuration can update the system prompt. After that, runtime user input shouldn’t modify it directly. Anyway, the point is: this provides solid protection.

Use both the API-level separation (role: system vs role: user) and structural delimiters like XML tags. Research shows neither is a hard security boundary on its own — OpenAI explicitly states that role levels “are not trust boundaries.” But layered together, they contribute to defense-in-depth. Anthropic specifically trains Claude to recognize XML tags as structural boundaries.

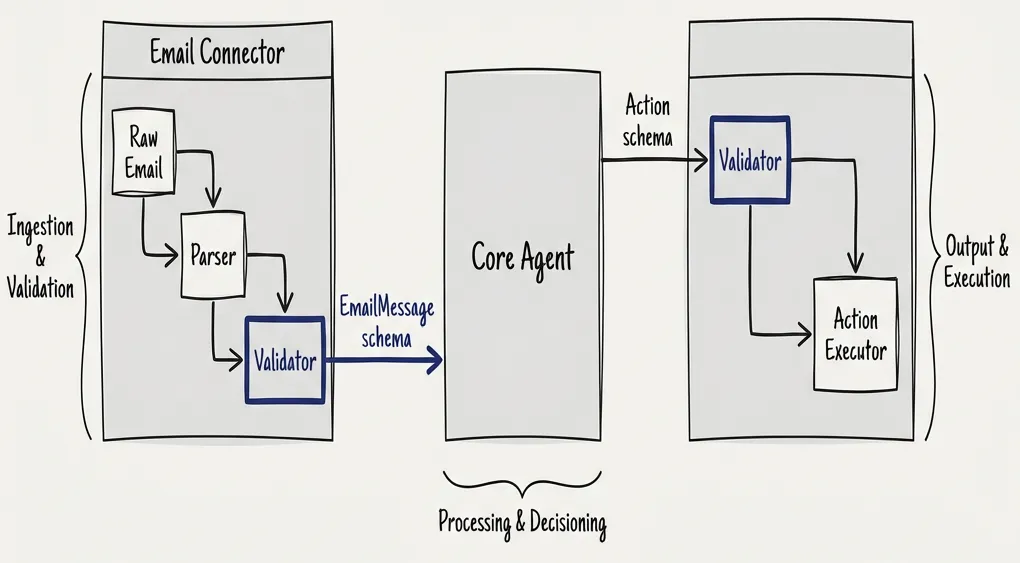

Structured Outputs: The Real Defense

The core defense pattern is structured outputs with schema validation. Every connector communicates through typed messages. No raw text flows through the system.

I prefer Pydantic for Python or Zod for TypeScript. The schema defines exactly what fields exist, what types they have, and what they mean. The only way a connector can communicate with the core — and vice versa — is through these structured messages.

Think of it like the App Store model. When you submit an application, Apple validates the binary, checks every API call you make, and provides only a constrained set of APIs and sandboxes. The same mental model applies here:

- Connector submits its schema

- System validates the schema claims

- Runtime enforces schema compliance

- No other communication path exists

When defining schemas, include not just the type but also what the field is for and how it can be used. This is what makes the rigid pieces of the system agentic-ready:

class ExtractedEmail(BaseModel):

sender_email: str = Field(description="Email address of sender, validated format")

sender_name: str | None = Field(description="Display name if present")

subject: str = Field(description="Email subject line, max 200 chars")

intent: Literal["inquiry", "support", "sales", "spam", "unknown"] = Field(

description="Classified intent based on content analysis"

)

key_facts: list[str] = Field(

description="Extracted factual claims, max 10 items, each max 100 chars"

)

# Note: original body is NOT passed to reasoning agentMulti-Stage Processing: Decoupling and Extraction

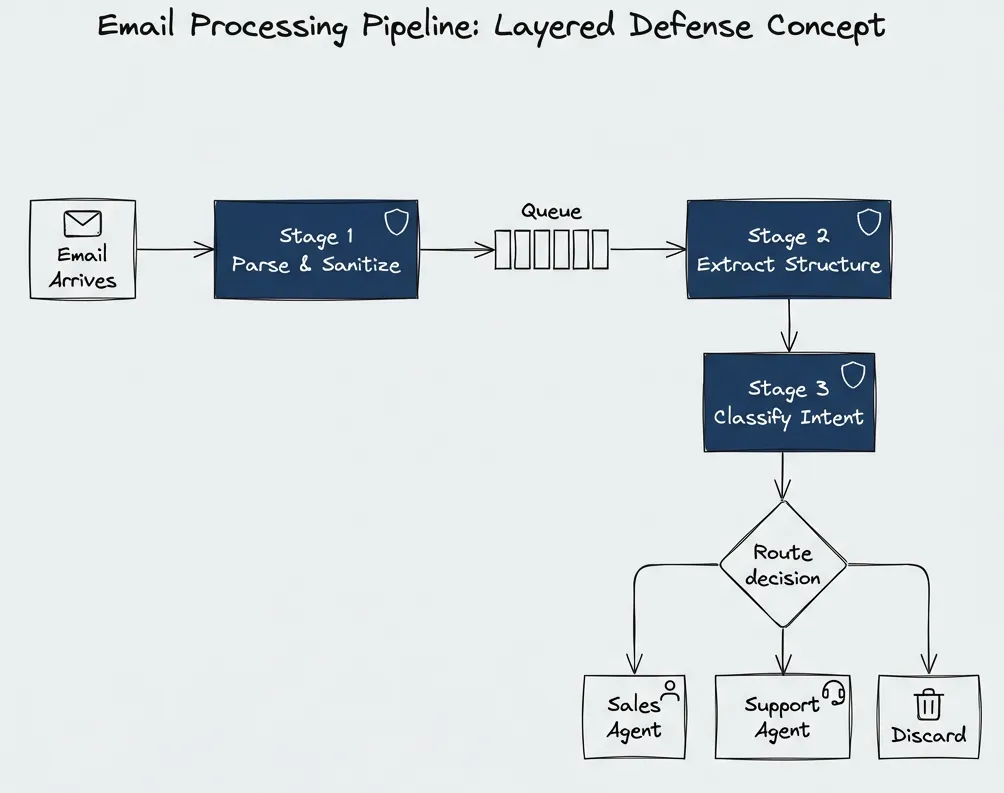

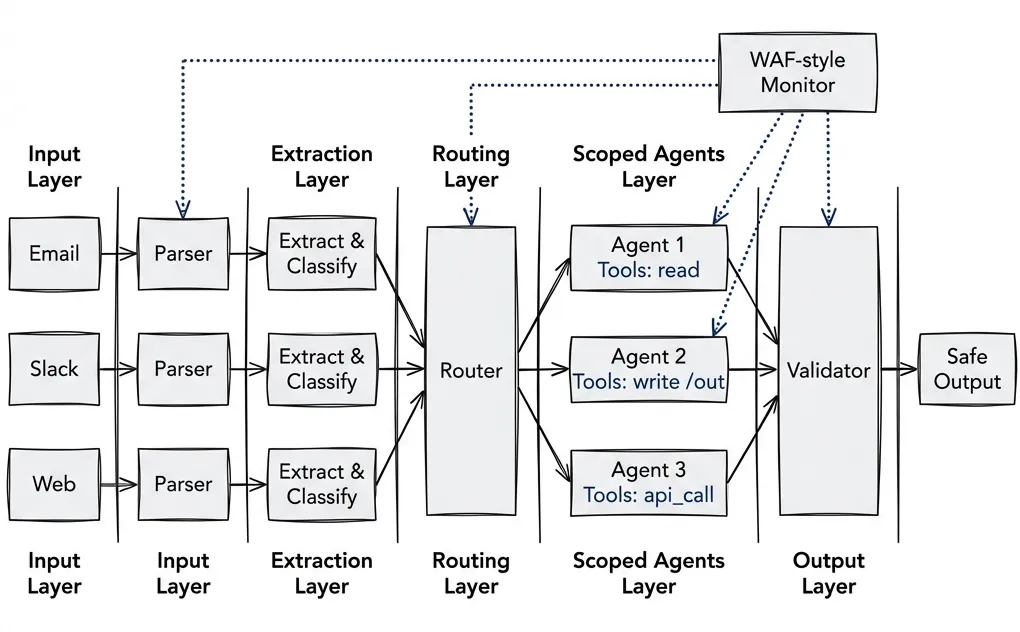

Research supports layered defense with multi-agent pipelines. Input undergoes sanitization both before and after processing. Each stage has limited context and limited tools.

For email processing, the pipeline looks like this:

Stage 1: Parse and sanitize. Extract sender, subject, basic metadata. Tools like HubSpot have done this for years — they know how to avoid injections. The output is structured data only.

Stage 2: Extract structure. Determine sender identity, intent, and key facts. Maybe include anchors to the original text for data lineage. A simpler, faster model can do this.

Stage 3: Classify and route. Based on extracted intent (not raw content), route to the appropriate handler. Each handler has its own constrained tool set.

The reasoning agent never sees the raw email. It sees extracted metadata and classified intent. Even if the original email contained injection payloads, they don’t survive multiple extraction stages.

This isn’t my invention — it aligns with OWASP LLM Security guidance, which recommends validating and sanitizing user inputs, using delimiters to separate instructions from data, and treating untrusted content as distinct from system instructions.

Input Validation: What Actually Works

Sanitization with regular expressions is naive for general text.

Modern LLMs understand dozens to hundreds of languages. Claude officially supports around 50, Gemini claims 100+. You can’t just filter English patterns and be fine. Attackers use Unicode obfuscation, mixed-language attacks, and encoding tricks. Regular expressions become useless for general content.

Where regex does work: fields where you know exactly what format to expect.

- Numbers only? Filter everything else.

- Email addresses? Validate format strictly.

- Flag base64 in fields where it shouldn’t appear.

- Strip XML/HTML tags from plain text fields.

For general text content, the defense is not trying to sanitize away all possible injection patterns. The defense is:

- Never let raw content reach the system prompt

- Use structured extraction to derive facts

- Let the reasoning agent work with derived data only

- Validate types at every boundary

The multi-agent defense research confirms this: “Input undergoes layered sanitization both before and after processing by agents, and potentially malicious content is masked to limit its influence on the LLM’s output.”

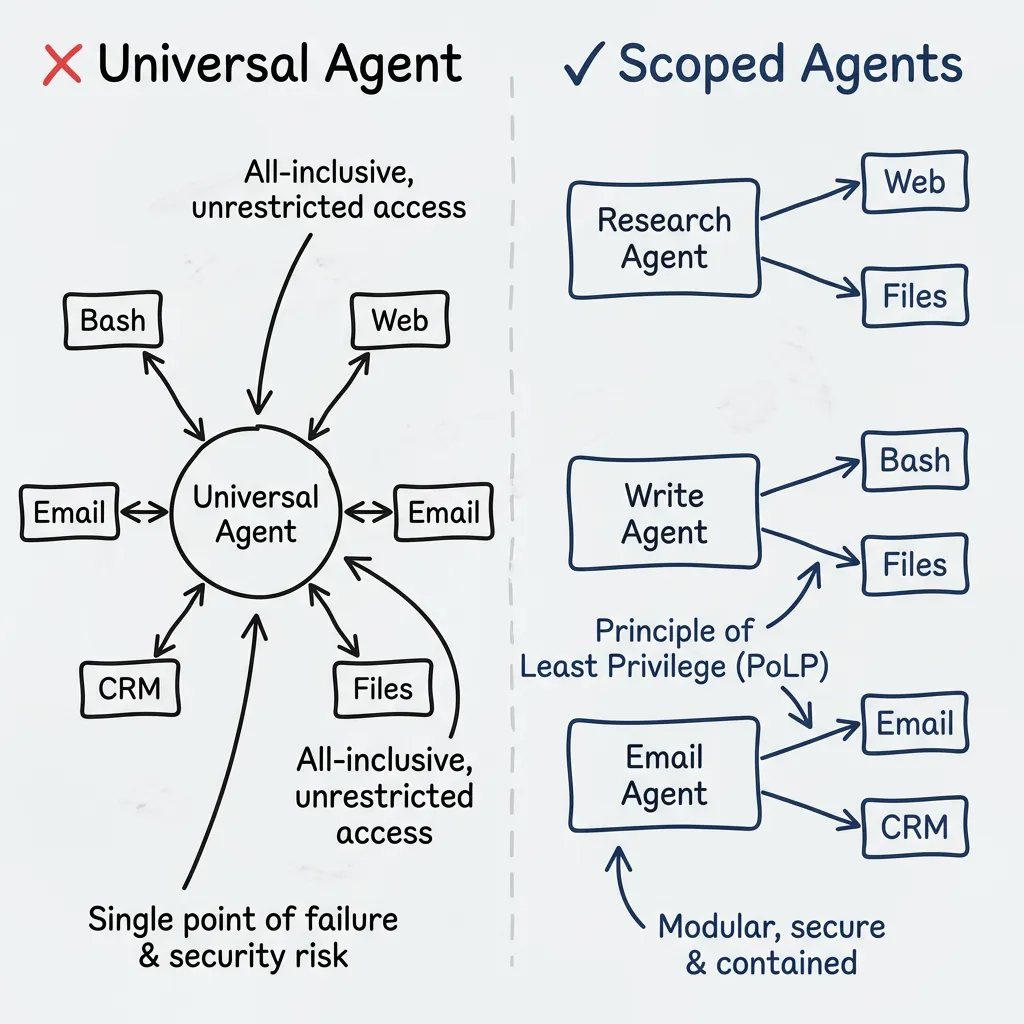

Least Privilege: Minimal Tools Per Stage

Each agent node should have access to only the tools it needs for its specific task. This is the principle of least privilege applied to LLM agents.

A universal agent — where after every tool call you return to the same agent that still has access to all tools — is the anti-pattern.

Instead:

- Research agent: read files only, restricted to specific directory

- Email processor: extract and classify only, no send capability

- Action executor: scoped write access, no network access

- Each stage passes structured output to the next

Even if there’s a vulnerability, it becomes impossible to exploit. Yes, you can send an email with a payload, but the system never downloads files from emails, never follows links, never places link content into the context.

The MiniScope paper from UC Berkeley makes this explicit: “Unlike prior works that enforce least privilege through prompting the LLM, our enforcement is mechanical and provides rigorous guarantees.”

This same principle — mechanical enforcement over prompt-based restrictions — applies to development workflows. Quality gates that reject bad code work because linters don’t negotiate. The agent can’t talk its way past a complexity threshold.

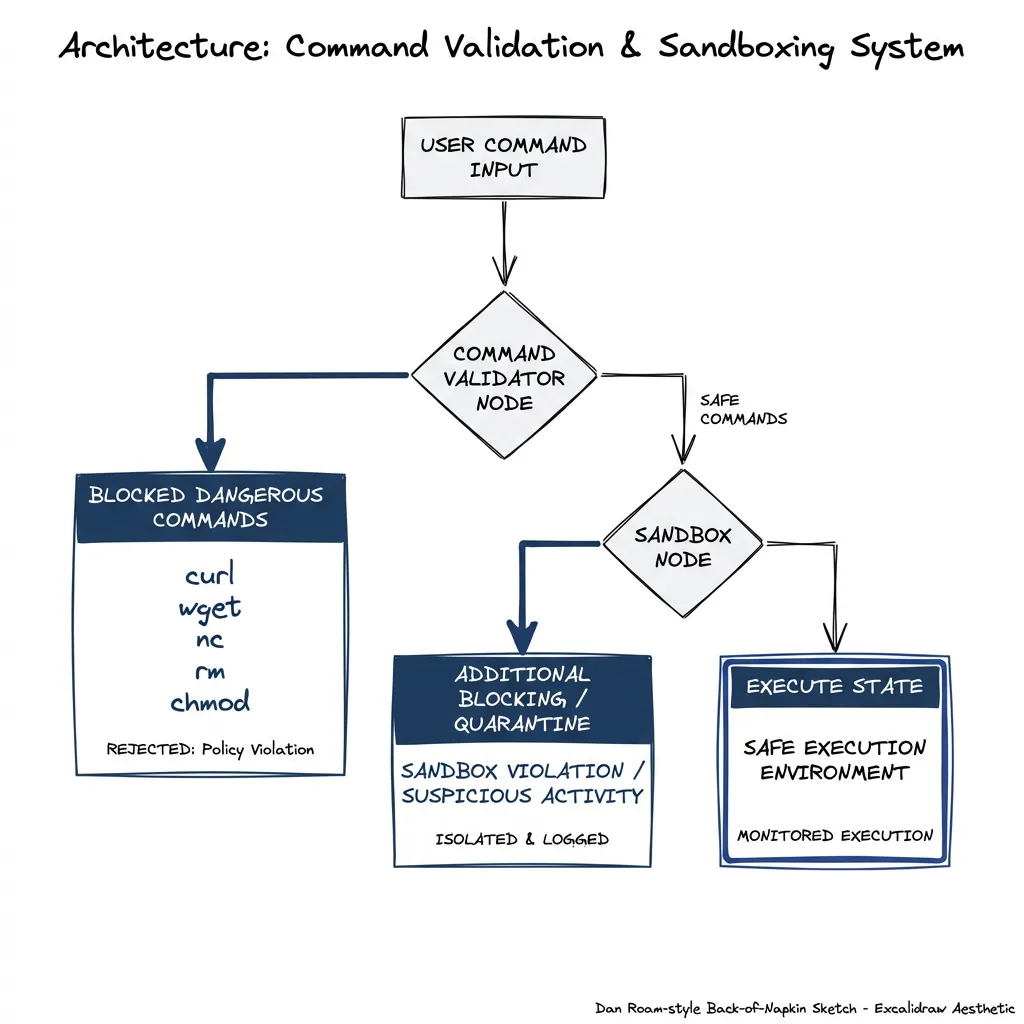

Why curl|bash Should Never Work

I was genuinely surprised — no, annoyed — that the curl|bash attack worked in ClawdBot. Claude Code, for comparison, has built-in sandboxing with OS-level enforcement for both filesystem and network isolation.

If you want to make bash available, you need mechanical enforcement, not prompt-based restrictions.

Options for safe bash access:

- No bash at all: If your agent doesn’t need shell access, don’t provide it. Seriously. Most don’t.

- Allowlist specific commands: But beware — allowlisting some commands is often equivalent to allowlisting all

- Sandbox with OS-level enforcement: Like Claude Code’s sandbox-runtime

- Deterministic execution only: Admin-defined scripts, not agent-composed commands

If you need shell commands, consider: can the administrator define the specific commands in advance? Then execute those deterministically rather than letting the agent compose arbitrary commands.

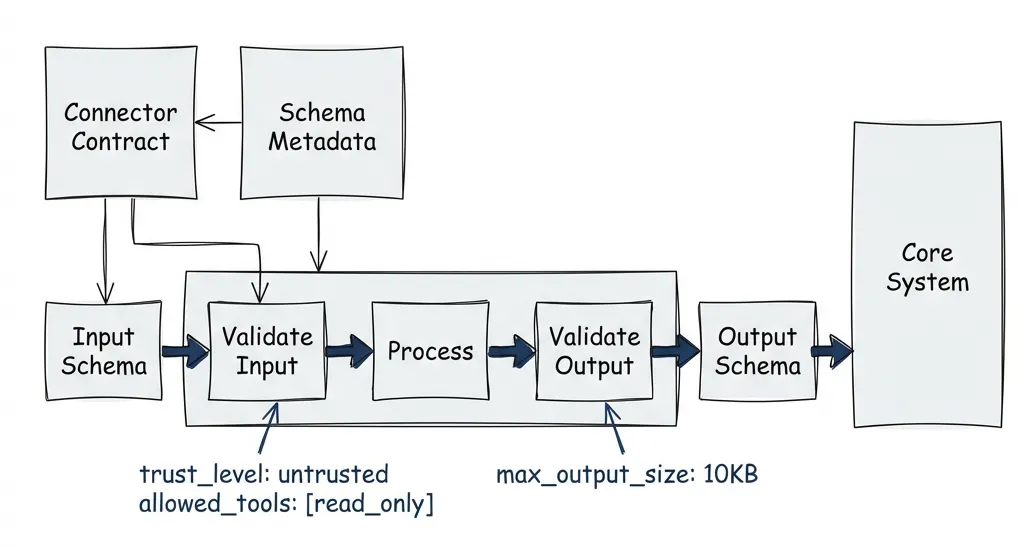

The Connector Contract

Each connector not only owns its security but describes exactly what messages it can send and receive. In TypeScript with Zod, the contract looks like this:

import { z } from 'zod';

// Every connector declares its contract upfront

interface ConnectorContract<TInput, TOutput> {

id: string;

version: string;

// Trust and permissions

trustLevel: 'untrusted' | 'verified' | 'internal';

allowedTools: readonly ('read_only' | 'write_scoped' | 'api_call')[];

// Schemas enforce structure at compile time AND runtime

inputSchema: z.ZodType<TInput>;

outputSchema: z.ZodType<TOutput>;

// Hard limits

maxOutputSizeBytes: number;

rateLimitPerMinute: number;

// The actual processor—sandboxed, with no access beyond declared tools

process: (input: TInput, ctx: SandboxedContext) => Promise<TOutput>;

}

// Example: inbound email connector

const EmailInboundSchema = z.object({

rawHeaders: z.record(z.string()),

rawBody: z.string().max(100_000), // Hard cap

receivedAt: z.string().datetime(),

});

const ExtractedEmailSchema = z.object({

senderEmail: z.string().email(),

senderName: z.string().max(100).optional(),

subject: z.string().max(200),

intent: z.enum(['inquiry', 'support', 'sales', 'spam', 'unknown']),

keyFacts: z.array(z.string().max(100)).max(10),

// Note: raw body is NOT in the output schema

});

const emailConnector: ConnectorContract<

z.infer<typeof EmailInboundSchema>,

z.infer<typeof ExtractedEmailSchema>

> = {

id: 'email-inbound-v1',

version: '1.0.0',

trustLevel: 'untrusted',

allowedTools: ['read_only'],

inputSchema: EmailInboundSchema,

outputSchema: ExtractedEmailSchema,

maxOutputSizeBytes: 10 * 1024,

rateLimitPerMinute: 100,

process: async (raw, ctx) => {

// Connector implementation here

// ctx only provides access to declared tools

}

};

When you accept a connector into your ecosystem, validation happens at multiple levels. At registration, you check that schema definitions are complete and typed. At runtime, every message gets validated against the declared schemas — if a connector tries to return something outside its contract, the message gets rejected before it reaches any agent.

This is the same model as mobile app stores. Apple checks the binary for every API call, provides only constrained APIs, and enforces sandboxes. I think the difference that matters: we can do this validation at the type level before anything runs.

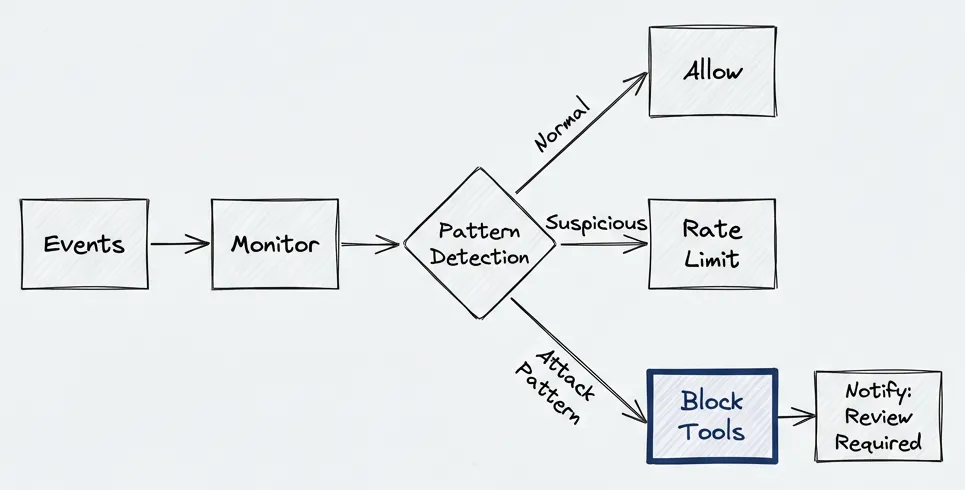

Monitoring: Treat It Like a WAF

Monitor events from every user and channel. If you see a repeated suspicious pattern over a short period, block that user’s tool calls.

The implementation doesn’t need to be complex. A sliding window counter per source is enough to catch most attack patterns:

type Decision = 'allow' | 'rate_limit' | 'block';

interface MonitorEvent {

sourceId: string; // email address, user ID, channel

eventType: string; // 'extraction_failure', 'tool_call', 'schema_violation'

timestamp: number;

metadata?: Record<string, unknown>;

}

class AgentMonitor {

private windows = new Map<string, number[]>();

private readonly thresholds = {

extraction_failure: { count: 5, windowMs: 60_000, action: 'block' as const },

tool_call: { count: 20, windowMs: 60_000, action: 'rate_limit' as const },

schema_violation: { count: 3, windowMs: 300_000, action: 'block' as const },

};

check(event: MonitorEvent): Decision {

const key = `${event.sourceId}:${event.eventType}`;

const now = Date.now();

const threshold = this.thresholds[event.eventType as keyof typeof this.thresholds];

if (!threshold) return 'allow';

// Get timestamps in window

const timestamps = this.windows.get(key) ?? [];

const recent = timestamps.filter(t => t > now - threshold.windowMs);

recent.push(now);

this.windows.set(key, recent.slice(-100)); // Keep last 100

if (recent.length >= threshold.count) {

this.notifyAdmin(event, threshold.action);

return threshold.action;

}

return 'allow';

}

private notifyAdmin(event: MonitorEvent, action: Decision) {

// Slack webhook, PagerDuty, whatever you use

console.warn(`[SECURITY] ${action} for ${event.sourceId}: ${event.eventType}`);

}

}What to watch for: repeated extraction failures from the same email address — someone’s probing your parser. Schema violations. High-frequency tool calls from a single source. In my experience, the extraction failures show up first.

When you detect attack patterns, disable tool use for that source:

“Sorry, there has been suspicious activity from your end. Tool use is disabled until reviewed by the system administrator.”

It’s not user-friendly, but it’s safer than letting anyone email you a payload that exports your client list.

The Architecture Summary

- Nothing influences the system prompt. Predefined modes only.

- Structured outputs everywhere. Typed schemas, validated at every boundary. This is the core defense — if you implement one thing from this post, make it this.

- Multi-stage extraction. Raw content never reaches reasoning agents.

- Least privilege tools. Each agent gets minimal required access.

- Mechanical enforcement over prompt-based restrictions. OS-level sandboxing where possible.

- Monitor like a WAF. Detect patterns, block suspicious sources, notify admins.

The Checklist

System Prompt Protection:

- No user input flows to system prompt

- Mode selection via predefined prompts only

Structured Communication:

- All connectors have typed schemas (Pydantic/Zod)

- Schema includes field descriptions and constraints

- Validation at every boundary

- No raw text passes between stages

- Output size limits enforced

Multi-Stage Processing:

- Extraction layer before reasoning

- Each stage has limited context and limited tools

- Raw content never reaches reasoning agent

Least Privilege:

- Each agent has minimal tool set

- Tools scoped to specific directories/APIs

- No universal agent with all tools

- Bash access sandboxed or eliminated

- Network access disabled where not needed

- File system access read-only where possible

Monitoring:

- Event logging from all stages

- Pattern detection for repeated failures

- Auto-block for suspicious sources

Use the Framework

That’s the theory. I wouldn’t have written it if I didn’t think it was solid.

But here’s the practical advice: use a fucking framework.

LangGraph. LangChain. CrewAI. AutoGen. These frameworks already enforce many of these patterns by design. Tool call safety. Contracts between nodes. Structured message passing. They don’t guarantee your code is safe, but they make it harder to screw up.

Same lesson we learned with web frameworks. Rails, Django, Laravel — they don’t eliminate SQL injection, XSS, or CSRF. But they make the secure path the default path. You have to actively work around the framework to introduce these vulnerabilities. The framework’s opinions push you toward correct code.

Same thing’s happening now with agents. As they get complex, there are a lot of questions to answer correctly. Without a framework, you either reinvent the wheel poorly or skip steps entirely. Frameworks encode solutions to problems you haven’t hit yet.

I use LangGraph — the graph model fits how I think about multi-stage pipelines. But the specific choice matters less than making one. Pick a framework. Learn its patterns. Let it guide your architecture.

Most of what I’ve described? LangGraph handles it for you. Typed state. Node isolation. Conditional routing. Tool scoping. You still need to think about security, but you’re not starting from scratch.

Twenty years ago, we learned to stop writing raw SQL. The solution wasn’t “be more careful” — it was parameterized queries, ORMs, frameworks that make the right thing easy.

The frameworks exist. Use them.

Sources:

- Simon Willison’s prompt injection research

- OWASP LLM Prompt Injection Prevention Cheat Sheet

- Multi-Agent LLM Defense Pipeline — Layered defense architecture

- MiniScope: Least Privilege for Tool Calling Agents

- Claude Code Sandboxing — OS-level enforcement

- Microsoft FIDES — Research on information flow control

- Google DeepMind CaMeL — Research on capability-based defense