You know what Winston Churchill used to say about Clay? That it’s the worst tool for GTM data management, except for all the others.

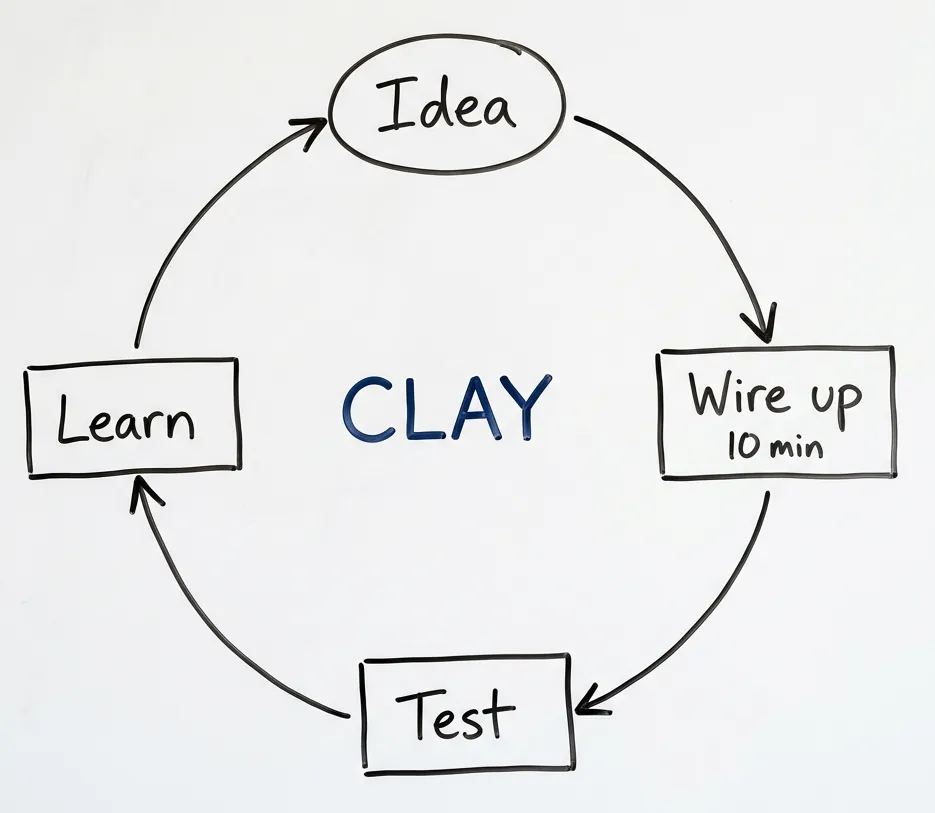

I use Clay every week. For testing enrichment flows, experimenting with prompts, stitching together data sources on the fly. Nothing beats it. My GTM engineer has a new hypothesis a couple times a week. He wires things up, runs them, experiments, thinks further, plans new things. That feedback loop? Can’t replace it.

And yet.

If you’ve ever posted “I’m getting duplicate rows of people” in the Clay community, this post is for you. If your lookup columns mysteriously stopped updating, or your webhook data just vanished, or your HubSpot sync keeps creating duplicates no matter what you try — you’re not doing it wrong. You’ve hit an architectural wall.

This isn’t a hit piece. It’s a mental model that will save you hours of frustration.

The one thing you need to understand

Here’s what explains almost every weird Clay behavior:

Rows don’t know about each other. Ever.

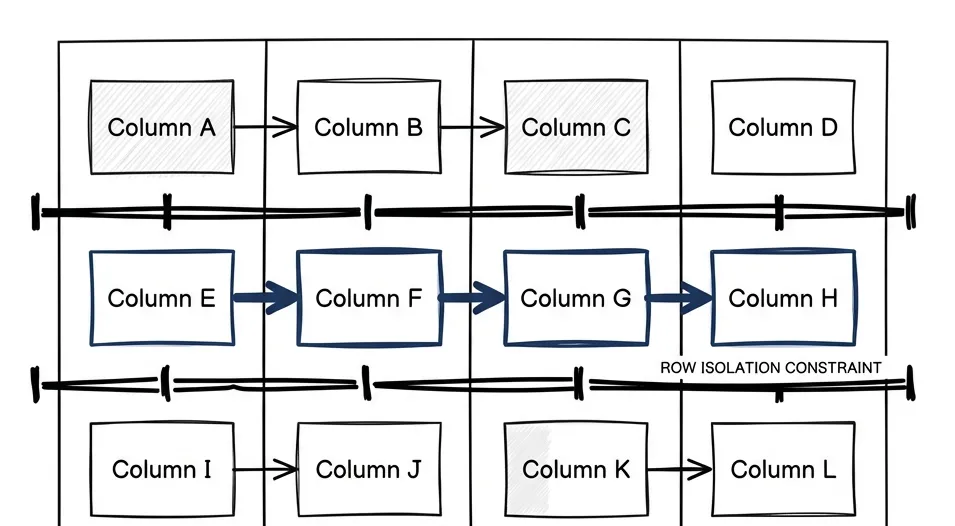

Columns know about each other, within the same row. You can reference any column from any other column, chain formulas, build dependencies. That’s fine.

But Row 1 has no idea Row 2 exists. There’s no way to write logic that says “before inserting this, check if a similar row exists and merge them” — and you can’t say “find the latest entry for this domain and update it” either. Cross-row awareness? Zero.

This is an architectural decision, not a bug. Clay is a spreadsheet with superpowers, and spreadsheets don’t assume database semantics. For rapid enrichment experimentation, this works.

For maintaining a source of truth about your prospects over time? Breaks everything.

The database normalization gap

Before I show you how this breaks, you need to understand why people don’t see it coming.

Foreign keys, primary keys, joins, deduplication. Classic database concepts. Second nature if you’ve worked with Postgres or even Excel power queries.

But most GTM engineers come from sales backgrounds. That’s not a criticism — the primary function of the job is understanding what customers want and how to get those signals. Sales intuition, not database design.

So when they hit these Clay limitations, they blame themselves. “I must be doing it wrong.” They’re not. Just hitting architectural constraints that’d be obvious to anyone who’s designed a database schema, but aren’t obvious at all if you’re thinking in spreadsheet terms.

The patterns we use in Clay — table lookups, normalization to avoid duplication, staging tables with formulas to pick the latest — are actually quite advanced. I wouldn’t call it engineering. I’d call it hacking around a tool that’s flexible enough to allow these hacks.

Still hacking though.

Why does Clay keep creating duplicates?

The most common complaint in the Clay community. Now that you understand row isolation, here’s why it happens.

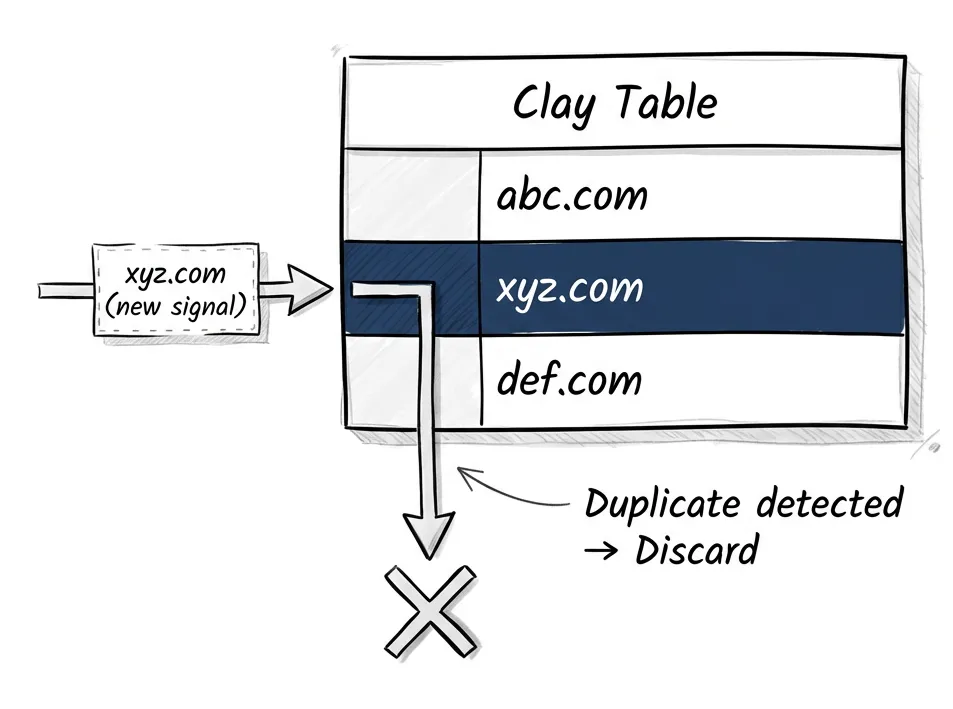

Clay has a deduplication feature. You can set any column to be deduplicated — typically domain or email. When a new row comes in, Clay checks: does this value already exist?

If yes, Clay discards the new row.

That’s it. No merge. No “keep the latest.” No “update these fields but preserve those.” Just discard. To merge, you’d need one row to know about another row. And rows don’t know about each other.

Here’s how this breaks in practice. You have a table of companies — you’ve researched them, enriched them, they’re sitting there with data. Now a webhook fires. Maybe a hiring signal, maybe a funding announcement. New data about xyz.com arrives.

Clay sees xyz.com already exists. Duplicate detected. New data discarded.

Your signal is gone. The system that was supposed to track changes just silently threw away the change.

The workarounds exist. You can create a staging table without deduplication, then use formulas to sort and pick the latest. You can build lookup chains. But every workaround adds fragility. The more steps you add, the harder it is for your team to maintain.

Why did my lookup stop updating?

This one drives people crazy because it feels like a bug. It’s not. Same architectural constraint, applied to related tables.

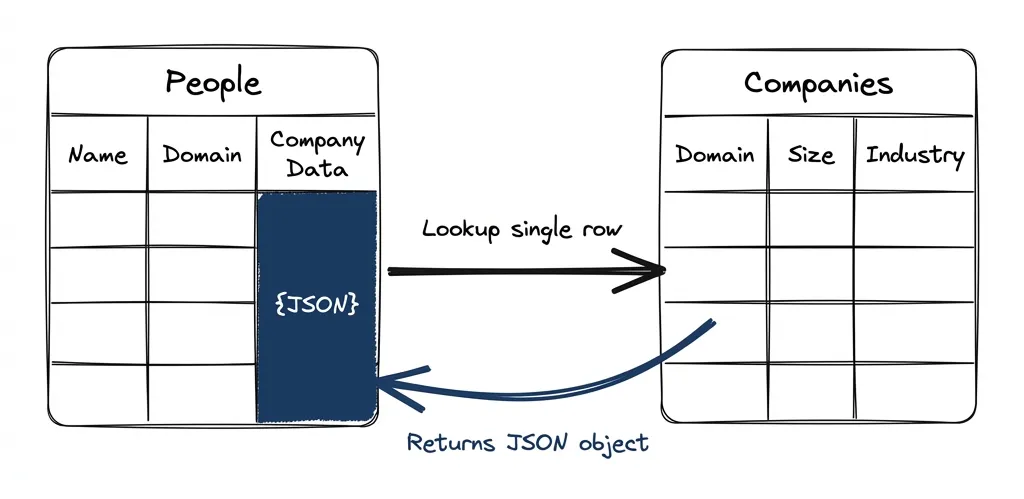

Here’s the scenario. You have a People table and a Companies table. You’ve connected them properly: each person row has a “lookup single row in Companies” enrichment that joins on domain. This gives you a JSON object containing all the company data. Smart — you’re not duplicating company data across every person row.

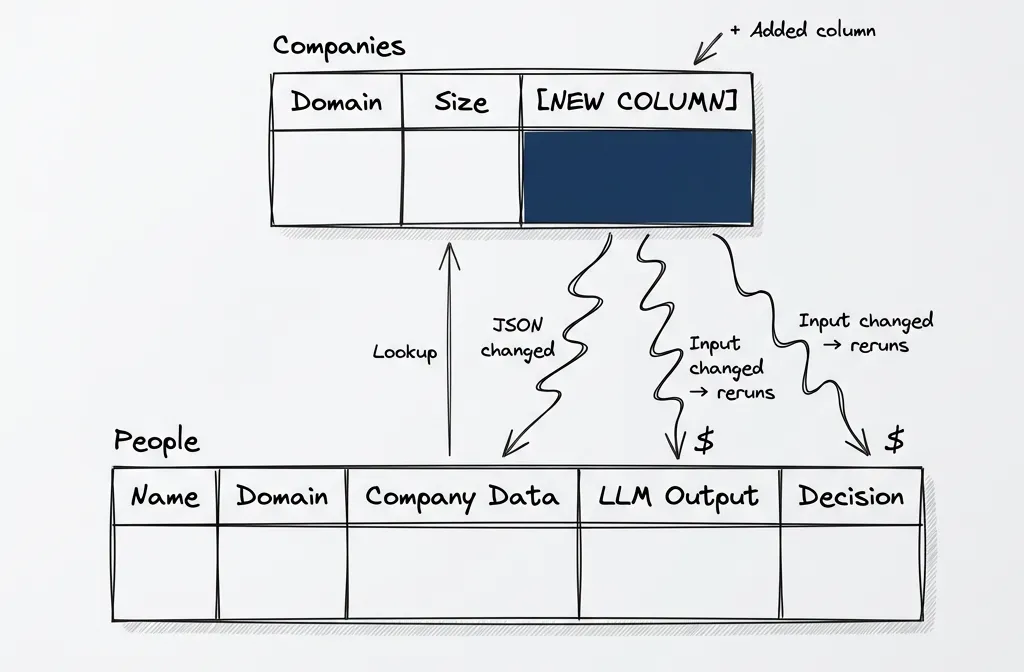

Now you realize you need a new column in Companies. Maybe company size, maybe a qualification flag. You add it.

You go back to People. The lookup column doesn’t have your new field.

To fix it, you have to rerun the lookup column. Here’s the cascade: when that lookup reruns, the JSON object changes (now has a new field). Any column that depends on that lookup — formulas, LLM prompts that take the company object as context — sees that its input changed. So those rerun too.

You just burned credits re-enriching rows where nothing meaningful changed. All because you added a column to a different table.

I understand why it works this way. The lookup returns an object, the object changed, downstream dependencies rerun. Technically correct. Also incredibly frustrating when you’re paying per enrichment.

Why your HubSpot sync creates duplicates

Same root cause, different symptom.

When you sync from Clay to HubSpot, you’re typically using “Create or Update.” The matching logic looks for an existing record by email or domain. If found, update. If not, create.

But if your Clay table already has duplicates — because deduplication just discards and there’s no merge — you’re syncing duplicates to HubSpot. Or if the matching field has slight variations (one row has “company.com”, another has “www.company.com”), you get two HubSpot records.

This also creates race conditions and rate limit errors. Apollo used to limit to 200 requests per minute. You send 300 rows, 100 will error out. Which 100? Random. Race conditions. Or two rows try to upsert into HubSpot at the same time, creating duplicates or conflicts.

The problem isn’t the sync. Clay has no mechanism to reconcile records before the sync happens. Each row is an island.

What Clay is actually great at

I don’t want to leave you thinking Clay is bad. It’s not. For one specific job, it’s the best tool I know.

That job is experimentation.

If you have an idea, you can wire it up in ten minutes. Want to test if job posting data from PredictLeads beats Google search? Set up a waterfall. Want to try a different classification prompt? Edit it live, run on ten rows, see results. Want to combine three data sources into a qualification score? Do it.

This speed matters. We’re limited human beings — we can’t imagine all the consequences of an idea until we try it. The value isn’t the automation you built. It’s the speed of the feedback loop. Ideas that fail? Fine. You tried, you learned, you moved on.

For connecting to many data sources, especially low-volume ones where a direct subscription doesn’t make sense, Clay is perfect. You can throw LeadMagic at it, Apollo, Google search, your own webhook — all in one flow. Pay per use. Don’t manage five different vendor relationships.

The flexibility and the number of connectors? I don’t know a better alternative.

The exclusion problem: when row isolation really hurts

Here’s where this gets worse over time.

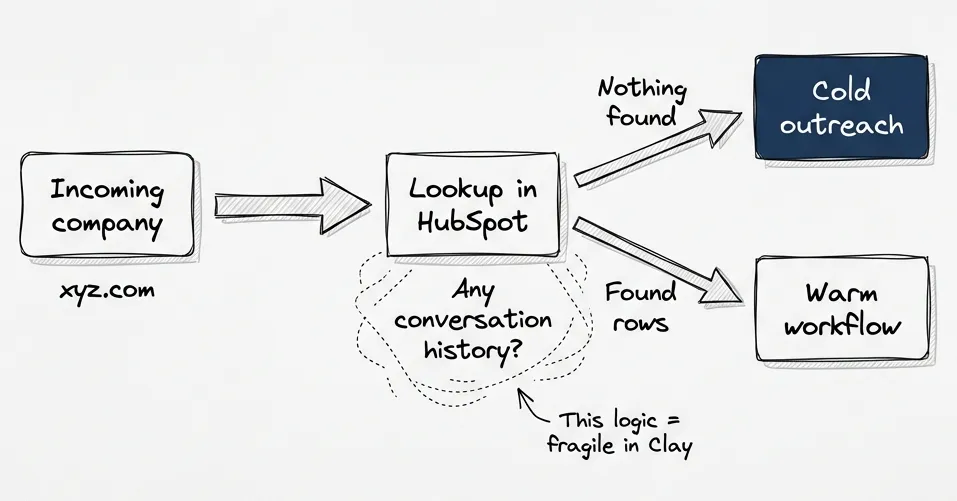

You work in a niche long enough, you’ve talked to maybe fifty companies already. At Postindustria, we definitely have — ad tech startups, partnerships, everyone. Not disqualified, just already warm. They shouldn’t get cold outreach, they should go to a different workflow.

But these companies keep reappearing. Every conference list, every association directory, every industry scrape. They’re there. We need a way to route them differently.

In Clay, this is hard. There’s no native way to say “check if this company exists in my CRM with conversation history and route accordingly.” You can do lookups to HubSpot, but the logic gets complex. You’re fighting the row isolation at every step.

One could argue that if we maintained lead statuses correctly in HubSpot, this wouldn’t happen. That’s true. But the point stands: Clay has no mechanism to help you reconcile records across sources. That’s not its job.

This is the pattern that made us realize we needed a layer outside Clay. Not because Clay is bad — because this isn’t what Clay is for.

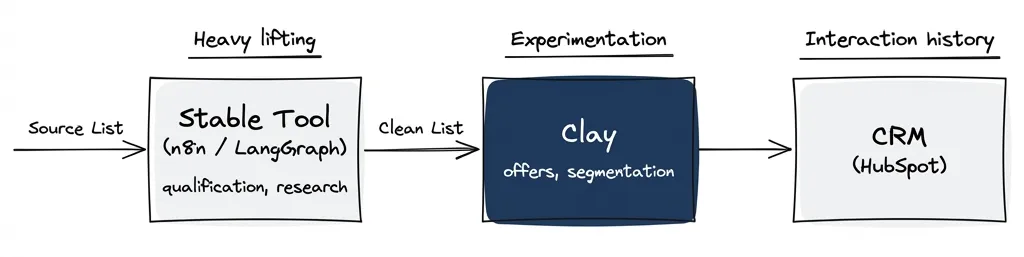

The real architecture

So what does work?

Clay for experimentation. A middle layer for truth. Your CRM for interaction history.

The middle layer does what Clay can’t:

- Merge records based on email or domain

- Update fields without rerunning enrichment

- Store research that took longer than 120 seconds

- Maintain history of what changed and when

- Route records based on cross-table logic

For us, this is Postgres with JSON fields. When Clay exports new data, a script merges it: new company? Insert. Existing company? Update the fields that changed. Conflicting data? Custom merge rules by field.

In practice, this is more than 200 lines of TypeScript. You’re also processing webhooks, doing statistics, synchronizing to HubSpot connected entities, pushing data into other systems. But it solves everything Clay can’t.

When to graduate a workflow

Not everything needs to leave Clay. The question is: has this workflow stabilized?

Here’s my rule. If the workflow changed a lot since last time — new data sources, different prompts, different logic — it’s still experimental. Keep it in Clay.

If it changed a little, or not at all, it’s stable. Time to graduate.

Stable chunks look like: that 4-5 column qualification check you set up every time (fetch jobs → LLM to extract signals → formula to decide). Or deep research that takes more than Clay’s 120-second timeout. Or the exclusion list routing.

These become part of your stable pipeline. n8n, Make, LangGraph — whatever you prefer. The honest truth: only LangGraph gives you full logging, history, and caching out of the box. The others are just cheaper. And n8n is notorious for hard debugging. When you try to handle unsuccessful scenarios, you go from a flow to an interconnected tree of subflows that no one can manage.

Clay stays for the flexible parts. For us, that’s offer creation — where we’re still experimenting. Everything upstream (qualification, routing, enrichment) has graduated.

The takeaway

For rapid experimentation and testing hypotheses fast, nothing beats Clay. The feedback loop is too valuable to give up.

But rows don’t know about each other. That single constraint means Clay can’t be your source of truth. It can’t track your prospects over time, merge records, maintain history, or route based on cross-table logic.

Use it for what it’s for. Build the middle layer for what it can’t do. Stop fighting the architecture.

If you’ve been using Clay for six months and something feels off — duplicates piling up, data not syncing right, workarounds getting fragile — you’re not imagining it. The architecture doesn’t support what you’re asking it to do.

Now you know why.

Next in the series: When to Move Off Clay — the practical migration guide for graduating stable workflows to n8n, Make, or LangGraph.